Prognostic factors on renal survival in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome

Renal survival in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome

Authors

Abstract

Aim Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome is the most common primary glomerular disease in children. The optimal therapeutic regimen for managing children at the onset and during idiopathic nephrotic syndrome is still under debate.

Methods A 10-year retrospective review of 185 children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome at the University hospital identified 125 eligible patients. At the last follow-up, they were classified as steroid- dependent, steroid-resistant, or in remission.

Results Steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome was observed in 27 patients (21.6%) and steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome in 34 patients (27.2%). Male predominance (M/F: 1.9) was consistent with the literature. Only 9 patients (7.2%) had no relapse after the first episode, while 64 patients remained in remission at the last follow- up. Sixty patients (48%) received at least one immunosuppressive agent other than steroids. Frequent relapses and steroid resistance were significantly more common in patients with obesity at diagnosis. Low albumin level at diagnosis, time to first remission, immunosuppressive drug use, pulse steroid requirement, hypertension, and macroscopic hematuria were significant prognostic factors for renal survival in patients in remission. The prognostic albumin cut-off value was 1.8 g / dL.

Conclusion Although it is hard to withdraw robust conclusions from our results, it might be thought that children with obesity, hypoalbuminemia (< 1.8 g / dL), and female gender seem to deserve closer follow-up and somewhat more aggressive management in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in terms of renal survival.

Keywords

Introduction

Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome (INS) is the most common primary glomerular disease in children 1. A minority of children with the condition have only a single episode (20-33%), with the remaining having, in order of increasing severity, infrequent relapses, frequent relapses, steroid dependence, or steroid resistance 2. The prognosis of children with INS mainly depends on the underlying histopathology and can be predicted by the response to steroid treatment 3. The optimal therapeutic regimen for managing children at onset and during INS is still under debate 4. The number of prospective or long-term studies on the subject is quite small. We retrospectively evaluated the demographic and prognostic features of 185 patients with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in our clinic.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective chart review of 185 children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome followed for 10 years in the Kocaeli University Faculty of Medicine Department of Pediatric Nephrology was done. Demographics, laboratory data, and prognostic factors were retrieved from the patients’ hospital records. Prenatal and natal histories and consanguinity of parents were noted. Preterm delivery was defined as births before the 38th week of gestation. All laboratory and clinical parameters that may affect prognosis were recorded. The reviewed data were age at presentation, gender, follow-up period, preterm delivery, oligohidramniosis, obesity, family history of kidney disease, hematuria, complement 3 (C3) level, albumin level at presentation, hypertension, acute kidney injury at onset, chronic kidney disease, first time in remission, pulse steroid and steroid sparing treatment, the longest remission time, renal biopsy and remission status at last visit. Predisease body weights were taken as the basis to determine the relationship between obesity and prognosis to exclude the impact of edema as a confounder at the time of diagnosis. After data collection, 60 patients who did not come to follow-up visits regularly or those with missing data were excluded from the study. Patients diagnosed with congenital nephritic syndrome and secondary nephritic syndrome were excluded from the study. The remaining 125 idiopathic nephrotic syndrome patients were included in the study. According to their status at last follow-up, patients were grouped as steroid dependent, steroid resistant, and in remission.

Treatment ProtocolAll patients initially were treated with prednisone (60 mg / m2 / day) for a full duration of 30 days, while relapses were treated with oral prednisone at 60 mg / m2 / day until remission plus 3 additional days. Then the prednisone dose was tapered to 40 mg / m2 every other day for 4 weeks, followed by a reduction of 10 mg / m2 every other day per week to the lowest dose required to maintain remission and ultimately, discontinuation of treatment if appropriate. Steroid-sparing agents were introduced if the patient presented with frequent relapses or steroid resistance.

Ethical ApprovalThis study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Kocaeli University, Faculty of Medicine (Date: 2019-01-04, No: 52).

Statistical AnalysisAll statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS for Windows version 22.0. Kolmogorov- Smirnov tests were used to test the normality of data distribution. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, median (25th-75th percentiles), and categorical variables were expressed as counts (percentages). The relationship between numerical variables was evaluated by Spearman Correlation Analysis. Receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis was performed to determine the cutoff value, sensitivity, and specificity of different cutoff points for albumin, first time in remission. The most appropriate cutoff point was chosen according to ROC analysis, and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated. Survival analysis according to albumin level and first remission time was performed with the Kaplan-Meier method. Two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Reporting GuidelinesThe study was conducted and reported in accordance with the STROBE guidelines.

Results

A total of 125 patients were included in the study with INS. Male / female ratio was 1.9 (82 / 43). While there was no significant difference between boys and girls for steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (SRNS), it was found that girls had a significantly increased risk for steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome (SDNS) development and frequent relapses (p < 0.05).

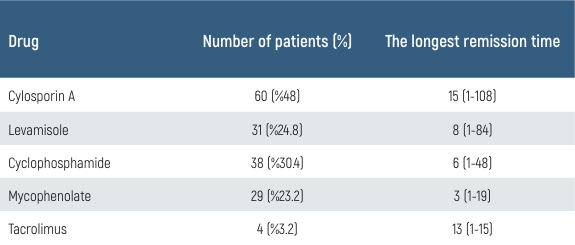

The median age of diagnosis was 48 months (12-192 months), and the mean follow-up period was 50 months (20-204 months). 11 patients (8.8%) had a history of premature birth (38 gestation weeks), and 29 patients (23.2%) had a family history of kidney disease. 12 patients (9.6%) had macroscopic hematuria, 9 patients (7.2%) had acute kidney injury, 8 of 12 patients with macroscopic hematuria developed SRNS (p < 0.001), but no significant difference was found in the development of SDNS. 31 patients (24.8%) required pulse steroid treatment at the time of diagnosis, and the risk of developing SRNS was significantly higher in these patients (p < 0.001). 23 patients (18.4%) had stage 2 hypertension at the time of diagnosis; the risk of developing SRNS was significantly higher in these patients (p < 0.001). 60 patients (48%) had used at least one additional immunosuppressive drug other than a steroid. The most common side effects of cyclosporine were hirsutism and gingival hypertrophy. These side effects improved with the discontinuation of the drug. Biopsy-proven nephrotoxicity developed in one patient out of 44 patients using cyclosporine (1.6%). Clinical details of each immunosuppressive drug are given in Table 1.

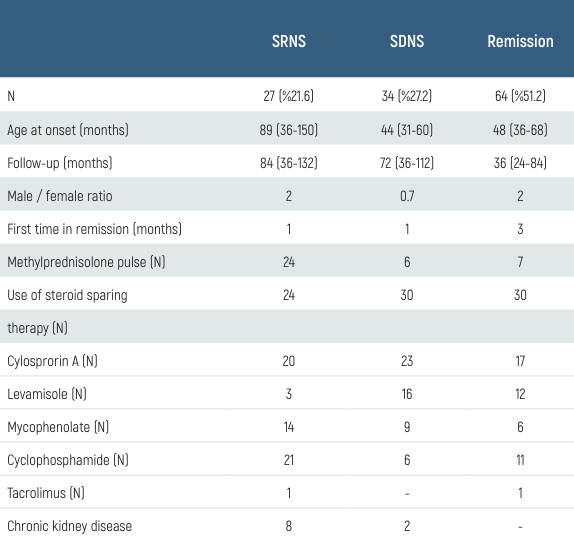

SRNS in 27 patients (21.6%), SDNS in 34 patients (27.2%), and chronic kidney disease (CKD) in 10 patients (8%) developed (Table 2).

The number of patients who did not relapse after the first episode was only 9 (7.2%). 64 patients were still in remission at the last clinic visit. Eight of 10 patients who developed CKD needed a pulse at the time of diagnosis, and 4 of 10 had macroscopic hematuria (p < 0.05). Of the 4 patients with end- stage renal failure, 1 patient was transplanted, and 3 patients are still undergoing hemodialysis. The histopathological findings of 66 patients who underwent kidney biopsy were as follows: 14 focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) (11.2%), 23 mesangioprolipherative glomerulonephritis (MesPGN) (18.4%), 29 minimal change disease (MDH) (23.2%). The baseline body weight of 64 patients (51.2%) was above the 90th percentile (p < 0.05). No significant relationship was found between obesity and SDNS, but the rate of frequent relapses and SRNS was significantly higher in patients with obesity at the time of diagnosis (p < 0.05). Two patients died (1.6%) because of cardiovascular complications.

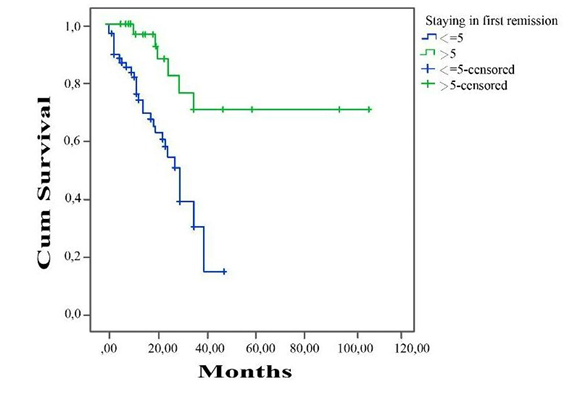

In our study, albumin level at diagnosis, first remission time, immunosuppressive drug use, pulse steroid requirement, accompanying hypertension, and macroscopic hematuria at diagnosis were found to be significant prognostic factors for renal survival in patients who were followed up in remission. The critical albumin level affecting prognosis was found to be 1.8 g / dL (cut-off point = 1.8 g / dL, AUC: 0.82, confidence interval (CI): 95%, 0.629 to 0.805, sensitivity = 85.00, specificity = 75.50, p < 0.05). Five-year renal survival was found to be 67% in patients with albumin level < 1.8 g / dL at time of diagnosis, and 89% in patients with albumin > 1.8 g / dL (Figure 1). Similarly, at the end of 5 years follow-up, remission rate of the patients achieving to stay in first remission shorter than 5 months was significantly lower than those who sustained their first remmision longer than 5 months (cut-off point = 5 months, AUC: 0.90 confidence interval (CI): 95% 0.70 to 0.81, sensitivity = 89.00, specificity = 51.50, p < 0.05) (Figure 2).

Discussion

Although idiopathic nephrotic syndrome is predominantly steroid- sensitive, the clinical importance and disease burden mostly stem from the development of frequent relapses, steroid dependence, or resistance 4,5. The lack of a clear consensus on the treatment of patients with SRNS and SDNS further complicates the situation. Steroids are the basis of the treatment, but the development of steroid dependence makes the management of INS difficult. Because of chronic steroid exposure, these children are at risk of serious complications necessitating steroid-sparing drugs as alternative therapy 2. The high risk of progression to chronic kidney disease in SRNS is another concern for these patients. So far, several prognostic factors for SRNS and SDNS development have been described in various studies 3,5.

In our study, we retrospectively examined clinical and laboratory parameters that may be effective on the prognosis of children with INS. Our results, in general, were in parallel with the literature. However, to the best of our knowledge, we encountered some parameters that were not previously reported. There was no correlation between age at presentation and future relapses among our patients, similar to the findings of Fujinaga et al 6. On the other hand, some studies found a significant correlation between age at presentation and an increased risk of frequent relapses 7,8. Again, male predominance (M / F: 1.9) in our study was inconsistent with the literature. While there was no significant difference between gender and the risk for SRNS development, we found that significantly more girls developed SDNS and frequent relapses than boys (p < 0.05). This result was contrary to the literature 7,9.

Macroscopic hematuria was highlighted by several studies, some of which said that the presence of hematuria was independently associated with late steroid resistance 8,10,11. Similarly, 8 out of 12 patients with macroscopic hematuria developed SRNS (p < 0.001). Another finding in agreement with the literature was the development of more SRNS in patients with hypertension at the time of diagnosis. Additionally, 31 patients (24.8%) required pulse steroid treatment at the time of diagnosis, and 60 patients (48%) required steroid-sparing drug; the risk of developing SRNS was significantly higher in these patients (p < 0.001). In many studies, the risk of SDNS development was reported to be high in patients with a first remission time of < 9 days 3,5. Due to missing data in hospital records of the patients, we could not make this analysis. But as for the relationship between the duration of staying in first remission and prognosis, patients staying in first remission.

There are a few studies investigating the relationship between obesity and prognosis. Current studies have shown that the incidence of ESRD in FSGS is higher in obese patients due to glomerulomegaly 12,13. Since there was an average edema-induced weight increase of 1.5 kilograms at the time of diagnosis, the latest known predisease healthy body weights were used for comparison. And in 64 patients it was > 75 percentile (p < 0.05). No significant relationship was found between obesity and SDNS development, but the rate of frequent relapse and SRNS was significantly higher in obese patients compared to normal weight patients (p < 0.05). To the best of our knowledge, this relation is reported for the first time in the literature. Given the limited number of published cases of obesity related SRNS and SDNS and that a significant number of them derive from autopsy studies, little is known about the outcome of these patients. Information about the clinical features that may distinguish these cases from INS is also scarce 12. Further research with larger number of patients are needed to be able to know for sure whether obesity is a true prognostic factor for SDNS or SRNS in INS. However, several studies have demonstrated that obese patients show characteristic haemodynamic changes of glomerular hyperfiltration, including vasodilation of glomerular afferent arterioles with increased glomerular filtration rates and increased filtration fraction 14,15. The characteristic insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia of obese patients could play a fundamental role in the pathogenesis of these haemodynamic changes 14,16. In addition, insulin can increase the synthesis of several growth factors that induce glomerular sclerosis and hypertrophy 17. In obese patients, the increased incidence of glomerulomegaly might be the factor facilitating proteinuria. However, edema is not apparent in obese patients despite nephrotic proteinuria. The reasons why obese patients with nephrotic proteinuria do not develop oedema are unknown. Some studies reported that patients with massive proteinuria but without hypoalbuminaemia, as in obese patients, as observed in hyperfiltering disorders, have significantly lower urinary excretions of N-acetyl-B-glucosaminidase and β2-microglobulin than patients with hypoalbuminaemia 12. These differences may suggest an altered tubular handling of filtered proteins in hyperfiltering disorders. In addition, the slow increase in proteinuria, characteristic of FSGS, may play an important role in the absence of hypoalbuminaemia and oedema, allowing compensatory mechanisms to counterbalance proteinuria 18.

With advancing technology, many novel markers that are thought to be effective at the molecular level of INS pathogenesis emerge in the literature, and their probable effects on the prognosis of INS are investigated. However, these tests are not widely available, and their cost is quite high, like soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR). Thus, easily available and cheaper alternatives like albumin are investigated in order to be used as a prognostic marker 19. In such studies, hypoalbuminemia has been shown to trigger thromboembolic events 20. In another study, low albumin level was associated with frequent relapses 21,22. In our study, we detected a statistically significant cutoff albumin level affecting the prognosis of 1.8 g / dL (p < 0.05). Five-year renal survival of the patients with albumin levels below this cutoff value was significantly lower than those above the cutoff (67% vs 89%) (p < 0.05). Similarly, patients with albumin < 1.8 g / dL had a significantly increased risk for SRNS and SDNS development compared to others (p < 0.05). This albumin cutoff might be clinically used as a prognostic factor in children with INS, but the need for confirmation by other studies is obvious.

At the end of the follow-up period, the number of patients who did not relapse after the first episode was 9 (7.2%), which is relatively low compared to the literature 1. This can be explained by the fact that mostly the complicated patients who frequently relapse or who are refractory to treatment are referred to our center.

The retrospective nature and some missing data in patient records are the weak points of our study. But, a relatively large sample size and a considerably long follow-up period might still render our results clinically usable in predicting the outcome of children with INS.

Limitations

Among the limitations of the study are its retrospective nature and the resulting lack of some patient data. More advanced results could have been obtained with a prospective study involving a larger number of participants.

Conclusion

Although it is hard to withdraw robust conclusions from our results, it might be thought that children with obesity, hypoalbuminemia (< 1.8 g / dL), and female gender seem to deserve closer follow-up and somewhat more aggressive management in INS in terms of renal survival.

Declarations

Ethics Declarations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Kocaeli University Faculty of Medicine (Date: January 4, 2019; Approval No: 52). The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Because of the retrospective design of the study, the requirement for informed consent was waived by the ethics committee.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

None.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.Ç., K.B.

Methodology: M.Ç., M.A.Ö.

Investigation: M.Ç., P.D.

Data curation: M.A.Ö., P.D.

Formal analysis: M.Ç.

Writing – original draft: M.Ç.

Writing – review & editing: K.B., P.D.

Supervision: K.B.

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content, including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, and some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents, and approval of the final version of the article.

Abbreviations

AUC: Area Under the Curve

CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease

ESRD: End-Stage Renal Disease

FSGS: Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis

INS: Idiopathic Nephrotic Syndrome

MesPGN: Mesangioproliferative Glomerulonephritis

ROC: Receiver Operating Characteristic

SDNS: Steroid-Dependent Nephrotic Syndrome

SRNS: Steroid-Resistant Nephrotic Syndrome

References

-

Dossier C, Delbet JD, Boyer O, et al. Five-year outcome of children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: the NEPHROVIR population-based cohort study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34(4):671-678. doi:10.1007/s00467-018-4149-2

-

Sureshkumar P, Hodson EM, Willis NS, Barzi F, Craig JC. Predictors of remission and relapse in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29(6):1039-1046. doi:10.1007/s00467-013-2736-9

-

Abdel-Hafez MA, Abou-El-Hana NM, Erfan AA, El-Gamasy M,, Abdel-Nabi H. Predictive risk factors of steroid dependent nephrotic syndrome in children. J Nephropathol. 2017;6(3):180-186. doi:10.15171/jnp.2017.31

-

Ali SH, Ali AM, Najim AH. The predictive factors for relapses in children with steroid- sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2016;27(1):67-72. doi:10.4103/1319- 2442.174075

-

Jellouli M, Brika M, Abidi K, et al. Nephrotic syndrome in children: risk factors for steroid dependence. Tunis Med. 2016;94(7):401-405.

-

Fujinaga S, Hirano D, Nishizaki N. Early identification of steroid dependency in Japanese children with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome undergoing short-term initial steroid therapy. Pediatr Nephro. 2011;26(3):485-486. doi:10.1007/s00467-010-1642-7

-

Andersen RF, Thrane N, Noergaard K, Rytter L, Jespersen B, Rittig S. Early age at debut is a predictor of steroid-dependent and frequent relapsing nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol.2010;25(7):1299-1304. doi:10.1007/s00467-010-1537-7

-

Sarker MN, Islam MM, Saad T et al. Risk factor for relapse in childhood nephrotic syndrome- a hospital based retrospective study. Faridpur Med Coll J. 2012;7(1):18-22. doi:10.3329/FMCJ.V7I1.10292

-

Noer MS. Predictors of relapse in steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2005;36(5):1313-1320.

-

Constantinescu AR, Shah HB, Foote EF, Weiss LS. Predicting first-year relapses in children with nephrotic syndrome. Pediatrics. 2000;105(3 Pt 1):492-495. doi:10.1542/peds.105.3.492

-

Sinha A, Hari P, Sharma PK, et al. Disease course in steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49(11):881-887. doi:10.1007/s13312-012-0220-4

-

Praga M, Hernández E, Morales E, et al. Clinical features and long-term outcome of obesity-associated focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(9):1790-1798. doi:10.1093/ndt/16.9.1790

-

Kambham N, Markowitz GS, Valeri AM, Lin J, D’Agati VD. Obesity-related glomerulopathy: an emerging epidemic. Kidney Int. 2001;59(4):1498-1509. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0590041498.x

-

Dengel DR, Goldberg AP, Mayuga RS, Kairis GM, Weir MR. Insulin resistance, elevated glomerular filtration fraction, and renal injury. Hypertension. 1996;28(1):127-132. doi:10.1161/01.hyp.28.1.127

-

Chagnac A, Weinstein T, Korzets A, Ramadan E, Hirsch J, Gafter U. Glomerular hemodynamics in severe obesity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;278(5):F817-F822. doi:10.1152/ ajprenal.2000.278.5.F817

-

Tucker BJ, Anderson CM, Thies RS, Collins RC, Blantz RC. Glomerular hemodynamic alterations during acute hyperinsulinemia in normal and diabetic rats. Kidney Int. 1992;42(5):1160-1168. doi:10.1038/ki.1992.400

-

Frystyk J, Skjaerbaek C, Vestbo E, Fisker S, Orskov H. Circulating levels of free insulin- like growth factors in obese subjects: the impact of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev.1999;15(5):314-322. doi:10.1002/(sici)1520-7560(199909/10)15:5<314::aid-dmrr56>3.0.co;2-e

-

Gyamlani G, Molnar MZ, Lu JL, Sumida K, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kovesdy CP. Association of serum albumin level and venous thromboembolic events in a large cohort of patients with nephrotic syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(1):157-164. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfw227

-

Peng Z, Mao J, Chen X, et al. Serum suPAR levels help differentiate steroid resistance from steroid- sensitive nephrotic syndrome in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30(2):301-307. doi:10.1007/s00467-014-2892-6

-

Mousa SO, Saleh SM, Aly HM, Amin MH. Evaluation of serum soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor as a marker for steroid-responsiveness in children with primary nephrotic syndrome. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2018;29(2):290-296. doi:10.4103/1319- 2442.229266

-

Jahan I, Hanif M, Ali MA, Hoque MM. Prediction of risk factors of frequent relapse idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Mymensingh Med J. 2015;24(4):735-742.

-

Dumas De La Roque C, Prezelin-Reydit M, Vermorel A, et al. Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: characteristics and identification of prognostic factors. J Clin Med. 2018;7(9):265. doi:10.3390/jcm7090265

Figures

Figure 1. Affect of abumin level on renal survival

Figure 2. First remission time and renal survival

Tables

Table 1. Longest remission time compared to immunosuppressive agents

Table 2. Clinical data and outcome of 125 children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Mehtap Çelakıl, Pınar Dervişoğlu, Merve Aktaş Özgür, Kenan Bek. Prognostic factors on renal survival in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Eu Clin Anal Med 2026;14(1):15-19

Publication History

- Received:

- December 12, 2025

- Accepted:

- December 31, 2025

- Published Online:

- December 31, 2025

- Printed:

- January 1, 2026