The effects of diabetes on the metabolism of the bone

Diabetes on the metabolism of the bone

Authors

Abstract

Mortality and morbidity in diabetic patients are influenced by a multitude of factors, including genetic sus- ceptibility, environmental influences, uncontrolled medical and surgical histories, and the impact of diabetes on bones and fractures. In type 1 diabetes (T1D), bone mineral density (BMD) tends to be low, elevating the risk of fractures. In type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), osteoblast function is impaired, leading to less mature bone formation, and accelerated bone resorption by osteoclasts. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that some an- tidiabetic medications may affect bone density. It is crucial to have updated screening and prevention programs in all countries where diabetes is increasing.

This paper will discuss the impact of diabetes mellitus on bone health to enhance understanding among stu- dents and healthcare workers.

Keywords

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic non-communicable disease that increases risk of bone fractures and osteoporosis. The consequences of type 1 diabetes on the bones are more severe than those of type 2 diabetes because insulin does not have an anabolic impact on bones. 1. Testing of bone mineral density (BMD) is the first step in detecting fracture risk and osteoporosis. BMD is a measure of the mineral content in bones that contributes to its strength. Recent studies consistently indicate that total body mineral density (TMD) is higher in type 2 diabetes and lower in type 1 diabetes 1,2. Many factors can make bones more likely to break or become weak, including how well you control your blood sugar, the severity and duration of disease, how often you fall, osteopenia, postural hypotension, medication side effects, vascular disease, and poor bone quality 3,4,5. Researchers in Rotterdam found that, compared to healthy controls, diabetics had a 69% higher incidence of fractures 6. T2DM and osteoporosis are chronic conditions, and the risk of developing either increases with age 7, more than 8.9 million fractures occur each year in women over the age of 50 due to both T2DM and osteoporosis 8. Lower BMD is a significant indicator of the increased risk of fractures in type 1 diabetes 9.

T1D causes hyperglycemia and early bone fragility as a novel consequence 10. However, Weber et al. demonstrated that the elevated risk of hip fractures in individuals with type 1 begins in early adulthood 11. Although fractures in type 2 diabetes are more common than in T1D 12, some possible reasons why people with type 1 diabetes may not have healthy bones include hyperinsulinemia, low levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 and vitamin D, poor metabolic management, vascular problems, and a high lipid profile 13. Clinical trials conducted on this topic thus far have either used too few patients or failed to record important details like metabolic control, insulin exposure, or hypoglycemia episodes 14. Due to better medical care, longer life expectancy has contributed to a significant increase in the overall number of people with type 1 diabetes who are in the age group most susceptible to fragility fractures 15. A study indicated that certain diabetes-related factors, such as the duration of the disease, the presence of neuropathy, and their HbA1c levels, may be used to assess a patient’s risk of fracture. Until recently, the mechanism behind the increased fracture risk was not well known 16.

The obesity epidemic and uncontrolled glycemic levels increase the incidence of type 2 diabetes and diabetic complications such as macrovascular disease, retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and fragility fractures, even though BMD was shown to be high in diabetic patients17,18. They also sustain fractures even at low-stress levels 19, which could explain the discrepancy between BMD and fracture incidence.

Bone strength is reduced in people with type 2 diabetes 20,21. Farr and his colleagues studied the bone quality in 2016 and they found that cortical thickness was thinner in diabetics compared to controls 22. The literature also showed that bone remodeling in diabetics is impaired, the cortical layer is thin and bone bending strength is low, thereby raising the susceptibility to fragility fractures 23,24,25. Particularly those of Latino and African American cultural heritage 24. Factors such as aging, corticosteroid use, sensory neuropathy, visual impairment, postural hypotension, and vascular disease are all linked to an increased risk of falls and bone fractures in diabetics, according to some evidence 19,26,27.

Why diabetes affects bone

All Diabetes patients have lower amounts of osteocalcin (OC), which plays an important role in energy metabolism, increases insulin sensitivity in muscle and adipose tissue, and promotes insulin secretion28,29,30. The literature shows that postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes had reduced levels of these indicators significantly, compared with controls 29. Some researchers discussed that people with type 2 diabetes have a lower level of the resorption marker, which is the serum C-terminal telopeptide from type 1 collagen, and high levels of sclerostin, which leads to fractures 30,31. Research indicates that high sclerostin levels are positively correlated with the duration of type 2 diabetes mellitus and glycated hemoglobin and negatively correlated with bone turnover marker levels by binding to the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LPR) 5 or 6, which suppresses the Wnt/ß-catenin pathway and adversely controls bone formation 31. It appears that hyperglycemia significantly impacts the vitamin D-calcium axis by reducing renal calcium absorption 32. The high glycemic levels impair the osteoblasts’ capacity to produce osteocalcin in response to 1,25(OH)2D3, which is at least partially explained by the decreased number of 1,25(OH)2D3 receptors on osteoblasts 32. Until now, it is unclear how vitamin D performs in type 2 diabetes and fracture risk 33. Diabetics also showed higher levels of circulating advanced glycation end products( AGE) 34. The interaction between AGEs and immunoglobulin increases vascular inflammation which leads to platelet and macrophage activation 33. As a result, bones become weak, and easily fractured and the macro- and microangiopathy worsens 35.

Anabolic hormones like growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) play an important role in the development of the bone and the maintenance of healthy bones thereafter 36. Some literature surveys show a higher risk of diabetes and metabolic syndrome in patients with low IGF-I serum levels and resulting in weaker bones in diabetics 37.

IGF-1 plays a role in reducing collagen degradation. There is strong evidence that IGF-1 is positively associated with bone mineral density (BMD) and inversely correlated with hip and vertebral fractures, according to studies 38,39.

Gut enteroendocrine K-cells in the duodenum secrete GIP, a hormone that regulates glucose levels; L-cells in the colon secrete GLP-1 and GLP-2, two hormones that regulate glucagon levels. The glands secrete GIP and GLP-1 shortly after food is consumed. After entering the bloodstream in an active hormonal state, they attach to specific G protein-coupled receptors located in different cells and target tissues 40. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) an enzyme is present in plasma and a wide range of tissues. It quickly breaks down and inactivates both hormones, which lowers their bioactivity 41. The incretin hormones GLP-1 and GIP hinder α-cells from releasing insulin by stopping them from producing glucagon 42. Both osteoblasts and osteoclasts express incretin receptors. These dietary hormones are known to be important in bone turnover because they suppress bone resorption the minute food is ingested. The continuous regulation of bone homeostasis is dependent on the communication between osteoblasts and osteoclasts 43,44. The gastrointestinal peptides GIP and, perhaps, GLP-1 and GLP-2, when consumed, may inhibit bone resorption and promote bone formation 45. Although GIP has dual action as an anabolic and antiresorptive hormone, research indicates that GLP-2, the antiresorptive hormone, may influence bone remodeling through decoupling bone resorption from other processes 46. Despite this, the precise mechanisms via which GLP-2 and GIP inhibit bone resorption are still a mystery. 47. Moreover, the effect of GLP-2 is still unknown, but endogenous GIP has an inhibitory impact on bone resorption in diabetic patients. Inconsistent evidence suggests that GLP-1 receptor agonists, which are used to treat obesity and type 2 diabetes, may slow bone loss. In addition to GIP, which is a key physiological regulator of bone loss after a meal, GLP-1 and GLP-2 may also have bone-preserving effects when given by medication. New approaches for treating and preventing skeletal fragility in diabetes could develop from a deeper comprehension of the effects of these gastrointestinal hormones on bone homeostasis in diabetic patients 48.

Figures

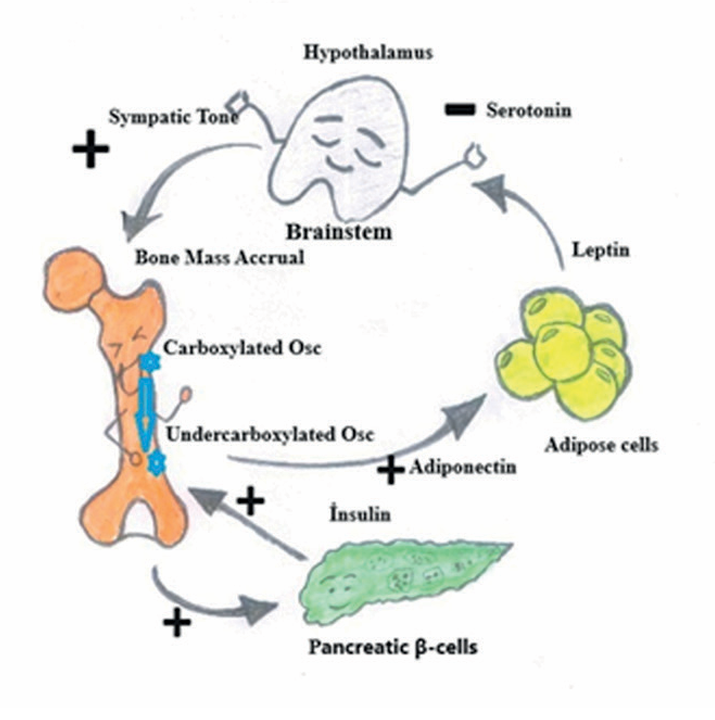

Figure 1. Sclerostin levels are negatively correlated with bone turnover and positively related with diabetes. Figure adapted from P. Ducy (Dia- betologia. 54:1291-7)

Tables

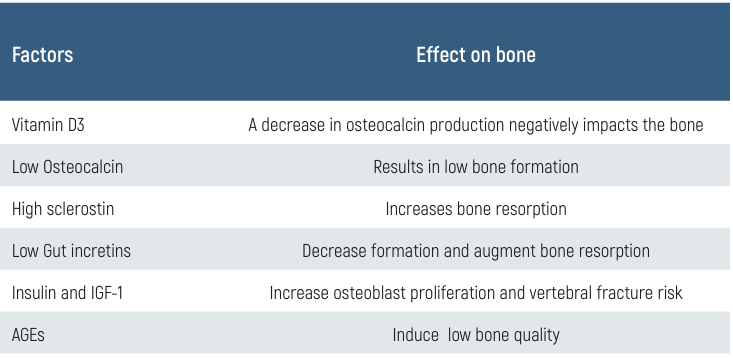

Table 1. Some factors and their effect on bone

Conclusion

The bone is considered an endocrine organ. There is a crucial link between bone, obesity, and glucose metabolism. High Insulin stimulates the secretion of undercarboxylated osteocalcin and sclerostin, small protein bone cells that respond to mechanical stress and regulate bone remodeling (Figure 1).

Measurements of bone mineral density (BMD) alone cannot predict fracture risk, especially in people with type 2 diabetes. A combination of many variables likely contributes to elevated risk (Table 1). A lower bone production rate, inferior bone quality, and an increased risk of fractures are all consequences of hyperglycemia. Reducing the production of AGEs, vascular damage in bone tissue, and the risk of falls are all possible outcomes of well-managed blood sugar levels, which aid in the prevention of fractures.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, due to privacy and ethical restrictions. The corresponding author has committed to share the de-identified data with qualified researchers after confirmation of the necessary ethical or institutional approvals. Requests for data access should be directed to bmp.eqco@gmail.com

References

-

Tomasiuk JM, Nowakowska-Płaza A, Wisłowska M, Głuszko P. Osteoporosis and diabetes - possible links and diagnostic difficulties. Reumatologia. 2023;61(4):294-304.

-

de Araújo IM, Salmon CE, Nahas AK, Nogueira-Barbosa MH, Elias J Jr, de Paula FJ. Marrow adipose tissue spectrum in obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;176(1):21-30.

-

Jackuliak P, Payer J. Osteoporosis, fractures, and diabetes. Int J Endocrinol. 2014:820615,10P.

-

Torpy JM, Lynm C, Glass RM. Osteopenia and Preventing Fractures. JAMA. 2006;296(21):2644.

-

Gilbert MP, Pratley RE. The impact of diabetes and diabetes medications on bone health. Endocr Ver. 2015;36(2):194–213.

-

De Liefde II, Van der Klift M, De Laet CEDH, Van Daele PLA, Hofman A, Pols HAP. Bone mineral density and fracture risk in type-2 diabetes mellitus: the Rotterdam study. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:1713–20.

-

Paschou SA, Dede AD, Anagnostis PG, Vryonidou A, Morganstein D, Goulis DG. Type 2 diabetes and osteoporosis: a guide to optimal management. J ClinEndocrinolMetab. 2017;102(10):3621–34.

-

Sanches CP, Vianna AG, Barreto Fd. The impact of type 2 diabetes on bone metabolism. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2017;9 (85):1-7.

-

Wierzbicka E, Swiercz A, Pludowski P, Jaworski M, Szalecki M. Skeletal status, body composition, and glycaemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Res. 2018;ID 8121634,14P.

-

Napoli N, Chandran M, Pierroz DD, Abrahamsen B, Schwartz AV, Ferrari SL, et al. Mechanisms of diabetes mellitus-induced bone fragility. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2017;13(4):208-19.

-

Weber DR, Haynes K, Leonard MB, Willi SM, Denburg MR. Type 1 diabetes is associated with an increased risk of fracture across the life span: a population-based cohort study using The Health Improvement Network (THIN). Diabetes Care. 2015;38(10):1913-20.

-

Ferrari SL, Abrahamsen B, Napoli N, Akesson K, Chandran M, Eastell R, et al. Bone and Diabetes Working Group of IOF. Diagnosis and management of bone fragility in diabetes: An emerging challenge. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(12):2585-96.

-

Maddaloni E, D’Eon S, Hastings S, Tinsley LJ, Napoli N, Khamaisi M, et al. Bone health in subjects with type 1 diabetes for more than 50 years. ActaDiabetol. 2017;54(5):479-88.

-

Mayer-Davis EJ, Lawrence JM, Dabelea D, Divers J, Isom S, Dolan L, et al. Incidence Trends of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes among Youths, 2002-2012. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(15):1419-29.

-

Starup-Linde J, Lykkeboe S, Gregersen S, Hauge EM, Langdahl BL, Handberg A, et al. Bone Structure and Predictors of Fracture in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes. J ClinEndocrinolMetab. 2016;101(3):928-36.

-

Ha J, Jeong C, Han KD, Lim Y, Kim MK, Kwon HS, et al. Comparison of fracture risk between type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a comprehensive real-world data. Osteoporos Int. 2021;32(12):2543-53.

-

Oei L, Rivadeneira F, Zillikens MC, Oei EHG. Diabetes, diabetic complications, and fracture risk. CurrOsteoporos Rep. 2015;13(2):106–15.

-

Wu B, Fu Z, Wang X, Zhou P, Yang Q, Jiang Y, et al. A narrative review of diabetic bone disease: Characteristics, pathogenesis, and treatment. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 14;13:1052592.

-

Oei L, Zillikens MC, Dehghan A, Buitendijk GH, Castaño-Betancourt MC, Estrada K, et al. High bone mineral density and fracture risk in type 2 diabetes as skeletal complications of inadequate glucose control. The Rotterdam study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(6):1619–28.

-

Liao CC, Lin CS, Shih CC, Yeh CC, Chang YC, Lee YW, et al. Increased risk of fracture and postfracture adverse events in patients with diabetes: two nationwide population-based retrospective cohort studies. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(8):2246–52.

-

Strotmeyer ES, Cauley JA, Schwartz AV, Nevitt MC, Resnick HE, Bauer DC, et al. Nontraumatic fracture risk with diabetes mellitus and impaired fasting glucose in older white and black adults. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(14):1612–17.

-

Farr JN, Khosla S. Determinants of bone strength and quality in diabetes mellitus in humans. Bone. 2016;82:28–34.

-

Wongdee K, Charoenphandhu N. Update on type 2 diabetes-related osteoporosis. World J Diabetes. 2015;6(5):673–78.

-

Moreira CA, Barreto FC, Dempster DW. New insights on diabetes and bone metabolism. J Bras Nefrol. 2015, 37(4):490–95.

-

Moreira CA, Dempster DW. Bone histomorphometry in diabetes mellitus. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(11):2559–60.

-

Gilbert MP, Pratley RE. The impact of diabetes and diabetes medications on bone health. Endocr Ver. 2015;36(2):194–213.

-

Melton LJ III, Leibson CL, Achenbach SJ, Therneau TM, Khosla S. Fracture risk in type 2 diabetes: Update of a population-based study. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(8):1334–42.

-

Rubin MR. Bone cells and bone turnover in diabetes mellitus. CurrOsteoporos Rep. 2015;13(3):186–91.

-

Shu A, Yin MT, Stein E, Cremers S, Dworakowski E, Ives R, et al. Bone structure and turnover in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(2):635–41.

-

Oz SG, Guven GS, Kilicarslan A, Calik N, Beyazit Y, Sozen T. Evaluation of bone metabolism and bone mass in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(10):1598– 604.

-

Canalis E. Wntsignalling in osteoporosis: Mechanisms and novel therapeutic approaches. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9(10):575–83.

-

Chaiban JT, Nicolas KG. Diabetes and bone: still a lot to learn. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab. 2015;13(1):20–35.

-

Manigrasso MB, Juranek J, Ramasamy R, Schmidt AM. Unlocking the biology of RAGE in diabetic microvascular complications. Trends EndocrinolMetab. 2013;25(1):15–22.

-

Epstein S, Defeudis G, Manfrini S, Napoli N, Pozzilli P. Diabetes and disordered bone metabolism (diabetic osteodystrophy): time for recognition. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27:1931–51.

-

Huebschmann AG, Regensteiner JG, Vlassara H, Reusch JEB. Diabetes and advanced glycoxidation end products. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(6):1420–32.

-

Locatelli V, Bianchi VE. Effect of GH/IGF-1 on Bone Metabolism and Osteoporosis. Int J Endocrinol. 2014;ID 235060,25P.

-

Friedrich N, Thuesen B, Jørgensen T, Juul A, Spielhagen C, Wallaschofksi H, et al. The association between IGF-I and insulin resistance: a general population study in Danish adults. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(4):768-73.

-

Niu T, Rosen CJ. The insulin-like growth factor-I gene and osteoporosis: a critical appraisal. Gene. 2005;361(1–2):38–56.

-

Garnero P, Sornay-Rendu E, Delmas P. Low serum IGF-1 and occurrence of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Lancet. 2000;355 (9207):898–9.

-

Mortensen K, Christensen LL, Holst JJ, Orskov C. GLP-1 and GIP are colocalized in a subset of endocrine cells in the small intestine. RegulPept. 2003;114:189–96.

-

Deacon CF. Circulation and degradation of GIP and GLP-1. HormMetab Res. 2004;36(11– 12):761–65.

-

Drucker DJ. The role of gut hormones in glucose homeostasis. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(1):24– 32.

-

Chen X, Wang Z, Duan N, Zhu G, Schwarz EM, Xie C. Osteoblast-osteoclast interactions. Connect Tissue Res. 2018;59(2):99-107.

-

Reid IR, Cornish J, Baldock PA. Nutrition-related peptides and bone homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;21(4):495–500.

-

Xie D, Zhong Q, Ding K-H, Cheng H, Williams S, Correa D, et al. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide-overexpressing transgenic mice have increased bone mass. Bone. 2007;40(5):1352–60.

-

Henriksen DB, Alexandersen P, Hartmann B, Adrian CL, Byrjalsen I, Bone HG, et al. Disassociation of bone resorption and formation by GLP-2: A 14-day study in healthy postmenopausal women. Bone. 2007;40(3):723–29.

-

Skov-Jeppesen K, Svane MS, Martinussen C, Gabe MBN, Gasbjerg LS, VeedfaldS, et al. GLP-2 and GIP exert separate effects on bone turnover: A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy young men. Bone. 2019;125:178-85.

-

Maagensen H, Helsted MM, Gasbjerg LS, Vilsbøll T, Knop FK. The Gut-Bone Axis in Diabetes. CurrOsteoporos Rep. 2023;21(1):21-31.

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or compareable ethical standards.

Funding

None

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Neveen Shalalfa, Saleh Shalalfa, Javid Mohammadzadeh Azarabadi, Ibrahim Alheeh. The effects of diabetes on the metabolism of the bone. Eu Clin Anal Med 2024;12(Suppl 1):S26-29

Publication History

- Received:

- August 1, 2024

- Accepted:

- October 8, 2024

- Published Online:

- October 18, 2024

- Printed:

- October 20, 2024