The role of gender-specific risk factors in coronary artery disease: Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention

Healthy lifestyle behavior scale II in CAD

Authors

Abstract

Aim This study aims to analyze the effect of gender-specific risk factors on diagnosis, treatment, and prevention strategies in coronary artery disease patients.

Material and Methods This descriptive cross-sectional study involved 1155 registered patients diagnosed with coronary artery disease (CAD) who were under treatment and follow-up at the Clinic over a 3-month period. The data were acquired through personal interviews, utilizing the sociodemographic form and the Healthy Lifestyle Behavior Scale II (HLBS II) related to patients’ sociodemographic characteristics.

Results Regarding age distribution, the largest proportion of patients (49.3%) fell within the 41-64 age range, while 39.6% were aged 65 and above. Upon analyzing the patients’ scores on the Healthy Lifestyle Behavior Scale II (HLBS II) by gender, the findings determined that men achieved higher average scores than women in the domains of spiritual development, interpersonal relations, and stress management. The average nutrition score in men was statistically lower than in women (p<0.05). Regarding age-related subscale scores, both physical activity and spiritual development scores declined with increasing age (p<0.05). There were statistically significant differences (p<0.05) among all age groups in terms of the physical activity subscale of the HLBS II. With respect to education levels, higher education was associated with a significant increase in average physical activity scores (p<0.05).

Discussion This study underscores the importance of acknowledging gender differences in cardiovascular diseases to improve diagnostic accuracy, treatment effectiveness, and preventive efforts. A comprehensive understanding of gender-specific nuances will pave the way for more personalized and effective cardiovascular healthcare strategies.

Keywords

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) pose a major global health challenge, with gender significantly influencing how the disease manifests, is diagnosed, treated, and approached in prevention strategies. Historically, cardiovascular research has been male-centric, but recent studies reveal that men and women experience CVDs differently. Gender differences in symptoms, risk factors, and treatment responses highlight the need for a gender-specific approach in healthcare 1,2. Gender-specific differences in CVDs are critical for improving diagnostic precision, as the manifestation of symptoms may be experienced differently between men and women. Understanding these differences allows for earlier and more accurate identification of at-risk individuals, enhancing patient outcomes 3,4.

Treatment strategies must also consider gender, as medications may have different efficacy and side effects based on sex, which underscores the importance of personalized treatment plans 5,6. Prevention strategies must address gender-specific risk factors, tailoring lifestyle modifications and early detection efforts to mitigate CVD incidence. Despite improvements in cardiovascular mortality rates, the burden of CVD remains high, particularly in countries like Turkey, where disparities in myocardial infarction rates, smoking prevalence, and sedentary behavior highlight the need for better adherence to prevention guidelines 7,8.

This research seeks to investigate the effects of gender-specific risk factors on the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of coronary artery disease, emphasizing the importance of gender in shaping cardiovascular healthcare strategies.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This cross-sectional descriptive study included 295 coronary artery disease (CAD) patients from the Cardiology Outpatient Clinic of Istanbul University Institute of Cardiology Hospital, covering February 15 to April 15, 2020. The study involved patients aged 12 and above, who were communicative, willing to participate, and diagnosed with CAD for at least 6 months. Participants with communication impairments or dementia were excluded. Data were gathered through face-to- face interviews using a Sociodemographic Information Form and the Health-Promoting Lifestyle Behavior Scale II (HLBS II).

Data Collection Tools

Updated in 1996 and validated by Bahar et al9, the HLBS II scale comprises 52 items across six sub-dimensions: interpersonal relations, spiritual development, nutrition, stress management, physical activity, and health responsibility. It is assessed using a 4-point Likert scale, with a Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of 0.92, demonstrating high reliability. The scale measures behaviors such as physical activity, nutrition, and stress management, with total scores ranging from 52 to 208, where higher scores indicate better health behavior implementation. Physical activity entails regularly engaging in light, moderate, and vigorous exercises. Nutrition determines an individual’s tendency to regulate, choose, and make food selections for their meals. Spiritual development focuses on the enhancement of internal resources. Growth involves working towards life goals and maximizing one’s strength for well-being. Interpersonal relations refer to relationships with others, requiring the use of communication to establish meaningful connections. Stress management involves an individual’s ability to identify and mobilize physiological and psychological resources to reduce or control tension. The scale’s sub-dimensions include the following items and score ranges: spiritual development with 13 items (min 13–max 52 points), health responsibility with 10 items (min 10–max 40 points), physical activity with 5 items (min 5–max 20 points), nutrition with 6 items (min 6–max 24 points), interpersonal relations with 7 items (min 7–max 28 points), and stress management with 7 items (min 7–max 28 points). The scale yields a total score that can range between 52 and 208. Higher scores reflect a greater adherence to health-promoting behaviors.

Measurements

The Sociodemographic Information Form collected data on patients’ accompanying chronic diseases, body mass index (BMI), body weight, height, age, gender, marital status, and education level. Body weight was measured using a calibrated scale, and height was determined with a stadiometer. BMI was then calculated and categorized according to WHO standards into normal weight, overweight, and obese categories. The stadiometer was aligned with the heels, gluteus, and back region, with feet together, arms at the sides, and the head in the Frankford plane. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated using the formula BMI (kg/m2) = Body Weight (kg) / Height (m2). Participants were then categorized based on the World Health Organization’s BMI categorization as follows: BMI 18.5-24.99 as normal weight, BMI 25-29.99 as overweight, and BMI ≥30 as obese.

Statistical Analysis

The data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 21. To evaluate data distribution, descriptive statistics were employed, and normality was confirmed through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Consequently, parametric tests were applied, including the independent sample t-test and One-way ANOVA, with Tukey’s post hoc test utilized for multiple comparisons. The study adopted a significance level of p<0.05.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the decision of the Ethics Committee of Health Sciences University (Date: 2020-01-29, No: 2020/15). The Declaration of Helsinki Protocol was followed in the research protocol.

Results

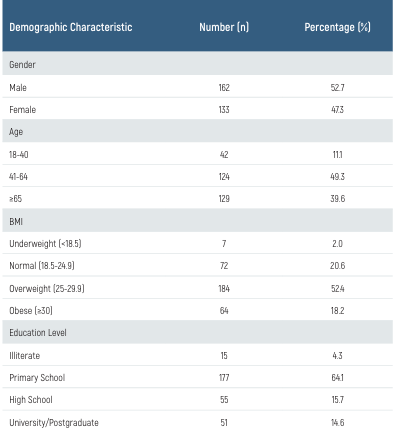

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the patients enrolled in the study. The gender distribution indicates that 52.7% of the participants were male, while 47.3% were female. Regarding age distribution, most patients (49.3%) were within the 41-64 age bracket, with 39.6% belonging to the ≥65 age group, and 11.1% being in the 18-40 age range. Regarding Body Mass Index (BMI), the highest percentage of patients were classified as overweight (52.4%), followed by those with a normal BMI (20.6%), obese individuals (18.2%), and underweight individuals (2.0%). When looking at the participants’ education levels, the largest proportion (64.1%) had finished primary school, followed by 15.7% who completed high school, 14.6% who had a university or postgraduate degree, and 4.3% who were illiterate.

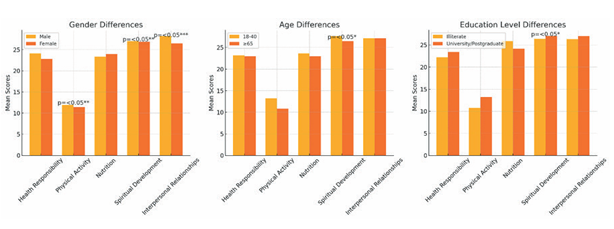

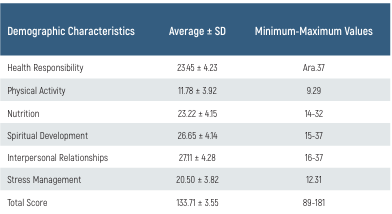

Table 2 shows the average scores for each sub-dimension. The typical score for patients on the Healthy Lifestyle Behavior Scale II (HLBS II) is 133.71 ± 3.55, with scores ranging from 89 to 181 (minimum-maximum values). Upon examining the average scores for the sub-dimensions of the HLBS II in this study, it was noted that interpersonal relationships had the highest score, whereas physical activity had the lowest. Table 3 highlights the relationship between demographic characteristics and the mean subscale scores of patients. Analyzing the HLBS II scores by gender found that men surpassed women in spiritual development, interpersonal relationships, and stress management (P<0.05). The average nutrition score was found to be lower in men compared to women, with this difference being statistically significant (p<0.05Analyzing the sub-dimension scores by age, it was noted that both physical activity and spiritual development scores declined as age increased (p<0.05). Post-hoc Tukey tests conducted after one-way ANOVA identified statistically significant differences (p<0.05) among all age groups in the physical activity sub-dimension of the HLBS II. No differences reached statistically significant in the total and sub- dimension scores across different BMI categories (p>0.05). When considering education levels, it was determined that as education level increased, the average scores for physical activity significantly increased (p<0.05) (Figure 1.).

Discussion

In our study, we conducted to determine the health-promoting lifestyle behaviors of patients diagnosed with coronary artery disease (CAD), the participants’ average total score on the Healthy Lifestyle Behavior Scale II (HLBS II) was found to be 133.71 ± 3.55. When reviewing the average total HLBS II scores reported in comparable studies, Nejati et al. 10 reported an average of 108.52 ± 5.45 for hypertensive patients, Kucukberber et al 11 reported 127 ± 21 for heart patients, Kilinc et al. 12 reported 130 ± 24 for heart failure patients, and Savasan et al. reported 128 ± 22 for coronary artery disease (CAD) patients 13. In our research, the raised average of the HLBS II total score is likely impacted by factors such as the participants being under follow-up for at least 6 months with a diagnosis of CAD, receiving information from healthcare professionals (physicians, nurses, dietitians, etc.) about their disease and its management 13. The study findings suggest that patients, upon receiving recommendations at the time of CAD diagnosis, effectively translate health-promoting behaviors into their lifestyles. Comparing the results with similar studies, it is believed that the guidance provided to patients at the time of CAD diagnosis contributes to the better incorporation of health-promoting behaviors into their lifestyles.

Upon analyzing the sub-dimension scores of the sub-dimensions by gender, it was observed that men had higher scores in spiritual development, stress management, and interpersonal relationships than women (p<0.05), while women scored lower on average in nutrition (p<0.05). In other studies, conducted with coronary artery disease (CAD) patients, similar to our study, men have been reported to have higher scores in spiritual development and stress management 14.

When comparing age groups, it was found that participants in the 18-40 years and 41-64 years groups showed higher mean scores in physical activity (p<0.05) and spiritual development (p<0.05) than those in the ≥65 years group (p>0.05). In their 2016 study, examining the effects of a healthy lifestyle on the quality of life in the elderly, Yilmaz and Çağlayan discovered that the elderly had a high average score in physical activity 15. On the other hand, Kulakci et al, and Polat et al determined in their studies that, similarly to the results of this research, the physical activity scores of elderly individuals were low 16,17. Cheong et al reported that older coronary artery disease patients had more healthy lifestyle behaviors 18. In a study conducted with university students, the physical activity sub-dimension had the lowest score, while the spiritual development sub-dimension had the highest. In our research, it was observed that younger patients had higher average scores in both physical activity and spiritual development (p<0.05) 19.

As individuals age, the emergence of deficiencies in the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems, the presence of various chronic diseases, and the decline in quality of life and physical activity are considered 20,21. Furthermore, the deficiencies are believed to contribute to everyday activities in the elderly, causing a reduction in independence. The high percentage of participants aged 65 and older in this study (36.50%) is seen as a factor leading to their lower scores in the physical activity sub-dimension 22.

In a study with hypertensive patients, similar to our research, the results indicated a high total score on the Healthy Lifestyle Behavior Scale II (HLBS II), with the lowest score obtained from the physical activity sub-scale 23. Chiou et al. (2016) reported findings similar to our study in research conducted with coronary artery disease patients, where interpersonal relationships had the highest average score, and physical activity had the lowest 14.

Education level has been reported to impact the adaptation to healthy lifestyle behaviors in patients with hypertension and heart failure 24. In a study involving patients who underwent coronary artery bypass surgery, those with higher education levels placed greater emphasis on healthy lifestyle behaviors 24. It was suggested that higher education enhances cognitive function and perception capacity, leading to a better understanding of the significance of lifestyle changes and the adoption of healthy lifestyle behaviors. According to a study with ischemic heart patients, as the level of education increases, the quality of life is also enhanced 25. In our study, as the educational level increases, greater average scores on the HLBS II are found.

Figures

Figure 1. Relationship Between Demographic Characteristics and Subscale Mean Scores of Patients

Tables

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Patients

Table 2. Average Scores of Healthy Lifestyle Behavior Scale II (HLBS II) for patients

Limitations

This study has certain limitations. The data is limited to a single center and the cross-sectional design restricts the ability to infer causality.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study revealed that women exhibit healthier meal selection, arrangement, and food choice habits compared to men. Men, however, presented greater proficiency in coping with stress and interpersonal relationships, along with higher levels of spiritual development. Participants scored highest in interpersonal relationships and lowest in the physical activity sub-dimension. The average physical activity score declined with age, but it increased in proportion to higher levels of education.

The findings suggest that environmental adjustments facilitating increased physical activity for elderly or physically impaired individuals could contribute to enhancing public health. Adherence to healthy living habits among individuals with coronary artery disease (CAD) would significantly contribute to improving their quality of life. Moreover, it is expected that educational programs provided by healthcare professionals will enhance individuals’ understanding of their conditions and promote adherence to healthier lifestyle behaviors.

It is promisin the note that higher education levels are positively correlated with increased scores in the physical activity sub-dimension. Thus, organizing educational programs specifically tailored to improve physical activity behaviors in individuals diagnosed with CAD is deemed beneficial. Continual monitoring of individuals is suggested to ensure the lifelong maintenance of healthy lifestyle behaviors. The findings of this study point to the vital role of customized educational programs in empowering individuals, especially those with CAD, to adopt and maintain healthy lifestyle behaviors.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, due to privacy and ethical restrictions. The corresponding author has committed to share the de-identified data with qualified researchers after confirmation of the necessary ethical or institutional approvals. Requests for data access should be directed to bmp.eqco@gmail.com

References

-

Al-Ajlouni YA, Al Ta’ani O, Shamaileh G, Nagi Y, Tanashat M, Al-Bitar F, et al. The burden of Cardiovascular diseases in Jordan: a longitudinal analysis from the global burden of disease study, 1990-2019. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):879-92.

-

Tannu M, Hess CN, Gutierrez JA, Lopes R, Swaminathan RV, Altin SE, et al. Polyvascular Disease: A Narrative Review of Risk Factors, Clinical Outcomes and Treatment. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2024;26(4):1-10.

-

Peng W, Jian W, Li T, Malowany M, Tang X, Huang M, et al. Disparities of obesity and non- communicable disease burden between the Tibetan Plateau and developed megacities in China. Front Public Health. 2022;10(1):1-9.

-

Rijal A, Nielsen EE, Adhikari TB, Dhakal S, Maagaard M, Piri R, et al. Effects of adding exercise to usual care in patients with either hypertension, type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57(14):930-9.

-

Li R, Shao J, Hu C, Xu T, Zhou J, Zhang J, et al. Metabolic risks remain a serious threat to cardiovascular disease: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Intern Emerg Med. 2024;19(3):1-9.

-

Ma M, He L, Wang H, Tang M, Zhu D, Sikanha L, et al. Prevalence and clustering of cardiovascular disease risk factors among adults along the lancang-mekong river: A cross- sectional study from low- and middle-income countries. Glob Heart. 2024;19(1):35-48.

-

Norris CM, Yip CYY, Nerenberg KA, Jaffer S, Grewal J, Levinsson ALE, et al. Introducing the Canadian Women’s Heart Health Alliance ATLAS on the Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Cardiovascular Diseases in Women. CJC Open. 2020;2(3):145-50.

-

Settelmeier S, Rassaf T, Hochadel M, Voigtlander T, Munzel T, Senges J, et al. Gender Differences in patients admitted to a certified german chest pain unit: Results from the German Chest Pain Unit Registry. Cardiology. 2020;145(9):562-9.

-

Bahar Z, Beşer A, Gördes N, Ersin F, Kıssal A. Sağlıklı yaşam biçimi davranışları ölçeği II’nin geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması. Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi Hemşirelik Yüksekokulu Dergisi [Validity and reliability study of the healthy lifestyle behaviors scale II. Journal of Cumhuriyet University School of Nursing.]. 2008;12(1):1-13.

-

Nejati S, Zahiroddin A, Afrookhteh G, Rahmani S, Hoveida S. Effect of group mindfulness- based stress-reduction program and conscious yoga on lifestyle, coping strategies, and systolic and diastolic blood pressures in patients with hypertension. J Tehran Heart Cent. 2015;10(3):140-8.

-

Kucukberber N, Ozdilli K, Yorulmaz H. Evaluation of factors affecting healthy life style behaviors and quality of life in patients with heart disease. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2011;11(7):619-26.

-

Kılınç G, Yıldız E, Kavak F. The relationship between healthy life style behaviors and hopelessness in patients with heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2016;7(13):114- 26.

-

Savaşan A, Ayten M, Ergene O. Koroner Arter Hastalarında Sağlıklı Yaşam Biçimi Davranışları ve Umutsuzluk [Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors and Hopelessness in Coronary Artery Patients]. Journal of Psychiatric Nursing/Psikiyatri Hemsireleri Dernegi. 2013;4(1):1-6.

-

Chiou AF, Hsu SP, Hung HF. Predictors of health-promoting behaviors in Taiwanese patients with coronary artery disease. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;30(4):1-6.

-

Yilmaz F, Çağlayan Ç. The effects of healthy lifestyle on the quality of life among elderly. Turkish Journal of Family Practice. 2016;20(4):129-40.

-

Kulakçi H, Emiroğlu ON. Impact of nursing care services on self-efficacy perceptions and healthy lifestyle behaviors of nursing home residents. Research in Gerontological Nursing. 2013;6(4):242-52.

-

Polat U, Ozen S, Kahraman BB, Bostanoglu H. Factors affecting health-promoting behaviors in nursing students at a university in Turkey. J Transcult Nurs. 2016;27(4):413-9.

-

Cheong E, Lee JY, Lee SH, Kang JH, Kim BS, Kim BJ, et al. Lifestyle including dietary habits and changes in coronary artery calcium score: A retrospective cohort study. Clin Hypertens. 2015;22(1):1-8.

-

Mak YW, Kao AHF, Tam LWY, Tse VWC, Tse DTH, Leung DYP. Health-promoting lifestyle and quality of life among Chinese nursing students. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2018;19(6):629-36.

-

Isanejad M, Steffen LM, Terry JG, Shikany JM, Zhou X, So Y, et al. Diet quality is associated with adipose tissue and muscle mass: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2024;15(1):425-33.

-

Nishikori S, Fujita S. Association of fat-to-muscle mass ratio with physical activity and dietary protein, carbohydrate, sodium, and fiber intake in a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):10631-35.

-

Briggs AM, Cross MJ, Hoy DG, Sanchez-Riera L, Blyth FM, Woolf AD, et al. Musculoskeletal health conditions represent a global threat to healthy aging: A Report for the 2015 World Health Organization World Report on Ageing and Health. Gerontologist. 2016;56(2):243-55.

-

Johnson JE, Gulanick M, Penckofer S, Kouba J. Does knowledge of coronary artery calcium affect cardiovascular risk perception, likelihood of taking action, and health-promoting behavior change?. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;30(1):15-25.

-

Zafari Nobari S, Vasli P, Hosseini M, Nasiri M. Improving health-related quality of life and adherence to health-promoting behaviors among coronary artery bypass graft patients: A non-randomized controlled trial study. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(3):769-80.

-

Huber A, Hofer S, Saner H, Oldridge N. A little is better than none: The biggest gain of physical activity in patients with ischemic heart disease. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2020;132(24):726-35.

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or compareable ethical standards.

Funding

None

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Health Sciences University (Date: 2020-01-29, No: 2020/15)

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Murat Bilgin, Ilker Gul, Emre Akkaya, Hamza Sunman, Recep Dokuyucu. The role of gender-specific risk factors in coronary artery disease: Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Eu Clin Anal Med 2024;12(3):46-49

Publication History

- Received:

- December 8, 2024

- Accepted:

- August 30, 2024

- Published Online:

- August 31, 2024

- Printed:

- September 1, 2024