The effect of patients’ education level on bowel preparation before a colonoscopy

The effect of education on colonoscopy

Authors

Abstract

Aim Colonoscopy is the most important method for diagnosing of colorectal cancers worldwide. One of the most important factors affecting the diagnostic accuracy of colonoscopy is proper bowel preparation. The aim of this study was to determine the effect of patients’ education level on bowel preparation before a colonoscopy. Material and Methods Patients who underwent colonoscopies performed by the same general surgeon between January and June 2021 were included in the study. Demographic data, including age, gender, and education level of the patients were recorded. Patients were divided into two groups according to their education level: those with low education level and those with high education level. The adequacy of bowel cleansing of the patients was determined by using the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS) 4. Patients with and without adequate bowel preparation were compared in terms of age, gender, educational status, and BBPS score.

Results* A total of 120 patients were included in the study. The mean age of the patients was 50.5 (±11.5) years. 54 (45%) were female and 66 (55%) were male. 32 of the patients had inadequate bowel preparation (26.7%). When classified by education level, 77 (64.2%) were included in group 1 (low education level) and 43 (35.8%) were included in group 2 (high education level). BBPS score was 7.1 (±1.9). The mean age was 49 years (±12.1) in patients with adequate bowel preparation and 54.5 years (±8.3) in those with inadequate bowel preparation (p=0.001). The number and proportion of patients with low education level were 52 (59.1%) among those with adequate bowel preparation and 25 (78.1%) in patients with inadequate bowel preparation (p=0.04).

Discussions The key factors affecting colon preparation are education level and age. It was found that bowel preparation before a colonoscopy was better in patients with higher education level and younger patients.

Keywords

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence varies by regions. Australia and New Zealand, Europe and North America have the highest incidence rates, while Africa and South-Central Asia have the lowest rates.1 These geographical differences are because of dietary and environmental factors, low socioeconomic status and low screening program rates. 2,3,4

Mortality rates from CRC have been decreasing in the United States and many other Western countries since the 1980s. This improvement can be attributed to the increased number of colonoscopies performed for screening and diagnostic purposes and the removal of colonic polyps and the earlier detection of CRCs. 5,6 Colonoscopy remains the most accurate and widely used method for the diagnosis of CRCs worldwide.

7 In addition to its visual diagnostic capabilities, the most important advantages of colonoscopy are that it is suitable for therapeutic procedures such as biopsy and even resection of polyps and early stage cancers.8 However, the diagnostic accuracy of colonoscopy depends on the quality of bowel preparation performed before the procedure. It has been shown in many studies that poor bowel preparation significantly hinders the diagnostic ability of colonoscopy. In some studies, it has been reported that especially small lesions could not be detected, and in others, it has been reported that poor bowel cleansing has a negative effect on the detection of all lesions, regardless of lesion size.9,10,11 It has been reported in some studies that not only the detection of lesions, but also the rate of performing a complete procedure in which the entire colon is examined is reduced, the procedure time is prolonged and the duration of anesthesia is prolonged. 11 As a result of the studies, the rate of poor bowel cleansing has been reported to be between 10% and 20% among patients undergoing colonoscopy.10,11,12,13

Various risk factors for poor bowel preparation have been identified. Time of colonoscopy onset, failure of patients to follow preparation instructions, inpatients, advanced age, cirrhosis, certain medications, male gender and various comorbidities have been found to be associated with inadequate bowel preparation in various studies 11,12,14,15. However, the education level of the patients was not emphasized in these studies. The aim of this study was to determine the effect of patients’ education level on bowel preparation before colonoscopy, which was not emphasized in previous studies.

Materials and Methods

Trial Design

This retrospective study was conducted at Health Sciences University Konya City Hospital, Department of General Surgery. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Participants, Eligibility Criteria and Outcomes

Patients who underwent colonoscopies performed by the same general surgeon between January and June 2021 were included in the study. All patients received the same standardized information from the same general surgeon and endoscopy nurse. The same medical method was applied to all patients for procedural preparation. Patients were given 500 cc of sennoside A+B between 19.00 and 22.00 hours the day before the procedure. In addition oral solutions, two 210 mL rectal enemas were administered. One enema was administered in the evening before the procedure and the other was administered the morning of the procedure. All patients were informed to stop consuming solid food 24 hours before the procedure and to consume plenty of clear liquids.

Inclusion criteria: patients who underwent colonoscopy on the specified dates, and were over 18 years of age.

Exclusion criteria: Patients under 18 years of age and those who underwent colonoscopy outside the specified dates.

Demographic data such as age, gender and education level of the patients were recorded. Patients were divided into two groups according to education level. Group 1 was defined as patients with low education level and group 2 as patients with high education level. Illiterate, only literate and primary school graduates were included in group 1, while those with higher education level were included in group 2.

The adequacy of the colon cleansing was determined using the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS) 4. According to the BBPS, 3 segments of the colon (left, transverse, right) are scored separately according to the degree of cleanliness and these scores are summed. Points are given according to the following conditions:

0 points: The colonic mucosa cannot be evaluated due to the presence of solid faeces,

1 point: Presence of faecal fluid and semisolid faeces in the colon segment,

2 points: Small amount of faecal fluid content allowing good evaluation of the mucosa,

3 points: Mucosa can be assessed as perfectly clean without any fluid residue.

According to the BBPS, a score of 0 indicates inadequate cleanliness and a score of 9 indicates perfect cleanliness. As the cleanliness score increases from zero to nine, it is understood that bowel cleanliness approaches perfection.16 Patients who scored 2 or more points for each of the three colon segments were considered having adequate bowel preparation, while those who scored less than 2 points per segment were considered to have inadequate bowel preparation.17 The study was completed by comparing the patients who were divided into two groups in terms of bowel preparation in terms of age, gender, educational status and BBPS score.

Statistical Analysis

At the beginning of the statistical analysis, Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk normality tests were performed. If normality was not achieved in any of the groups, non-parametric methods were used. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the variables obtained by measurement between the groups. Chi-square and Fisher’s Extract tests were used to analyze associations or differences between groups for categorical variables. Comparative results between groups and other demographic characteristics were presented using the ratios of qualitative variables. Quantitative variables were presented as the mean (standard deviation). The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the analysis and p < 0.05 was considered the threshold for statistical significance.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Hamidiye Scientific Research Ethics Committee (Date: 2024-08-22, No: 24/430).

Results

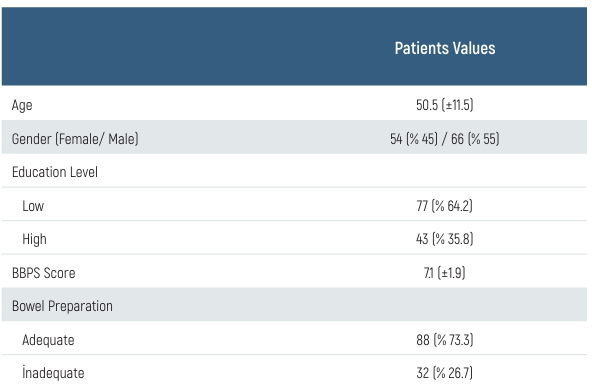

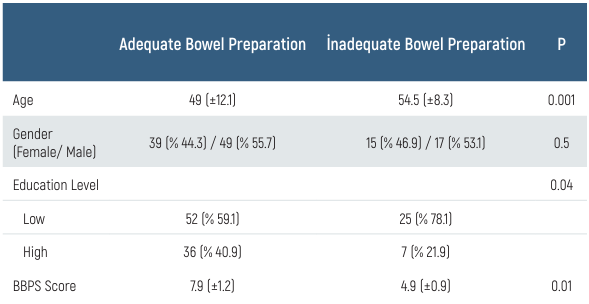

Between January and June 2021, 120 patients who underwent colonoscopy performed by a designated specialist were included in the study. The mean age of the patients was 50.5 (±11.5) years. 54 (45%) were female and 66 (55%) were male. 32 of the patients had inadequate bowel preparation (26.7%). When classified by education level, 77 (64.2%) were included in Group 1 (low education level) and 43 (35.8%) were included in Group 2 (high education level). BBPS scores were 7.1 (±1.9) (Table 1). The patients were divided into two groups as adequate and inadequate bowel preparation and the groups were compared. The mean age was 49 years (±12.1) in patients with adequate bowel preparation and 54.5 years (±8.3) in patients with inadequate bowel preparation. (p=0.001) The number of female patients was 39 (44.3 %) and 49 (55.7 %) in patients with adequate bowel preparation, while the number of female patients was 15 (46.9 %) and 17 (53. 1). (p=0.5) The number and proportion of patients with low education level was 52 (59.1%) in patients with adequate bowel preparation and 25 (78.1%) in patients with inadequate bowel preparation (p=0.04). The mean BBPS score was 7.9 (±1.2) in patients with adequate bowel preparation and 4.9 (±0.9) in patients with inadequate bowel preparation. (p=0.01) (Table 2)

Discussion

Colonoscopy is the most important tool for diagnosing and following up of colorectal cancers. Many factors affect the diagnostic power of colonoscopy. Selehi et al. reported that the most important factors preventing a complete colonoscopy were poor bowel preperation and excessive looping of the intestines.18 In addition, many studies have reported that the most important factor affecting the diagnostic power of colonoscopy is good bowel preparation.19,20 Although different rates were reported in previous studies, the rate of patients with inadequate bowel preparation ranged between 10% and 25%.13 In our study, this rate was found to be 26.7%, which is close to the literature.

While diagnostic colonoscopy depends on a good bowel preparation, various factors affecting bowel preparation have been defined. Previous studies have reported that the factors affecting bowel preparation include the timing of colonoscopy onset, failure of patients to comply with preparation instructions, inpatient procedures, elderly patients, cirrhosis, some specific drugs used, male gender and various morbidities.11,12,14,15 Lebhowl et al. also reported that increasing age and male gender were risk factors for inadequate bowel preparation in their study. 21 Increasing age is known to be associated with prolonged colon transport time, more comorbidities and higher drug use, and these are thought to have a negatively affect bowel preparation.22 In our study, the age of patients with inadequate bowel preparation was found to be significantly higher. However, no significant difference in gender was found between the groups in our study.

Another factor discussed in relation to bowel preparation is the educational level of patients. In a study conducted by Chan et al., low education level, a waiting time for colonoscopy longer than 16 weeks and non-compliance with bowel preparation instructions were found to be independent risk factors for poor bowel preparation. 23 Serper et al. reported that education level and health literacy were not among the independent risk factors for poor bowel preparation as a result of multivariable analysis. 24 A study conducted in our country reported that education level had no effect on bowel preparation.25 It is seen that there is no consensus in the literature about the effect of patients’ education level on bowel preparation. In our study, it was found that BBPS score was significantly lower in patients with a low education level and bowel cleansing was inadequate in these patients. This suggests that patients with higher education level understand and perform bowel preparation procedures better and patient compliance with colonoscopy procedures increases.

Tables

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics and Colonoscopy Parameters of All Patients

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, median and frequency. BBPS: Boston Bowel Preparation Scale

Table 2. Comparison of Groups According to Bowel Preparations

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation and frequency. BBPS: Boston Bowel Preparation Scale

Limitations

The most important limitations of the study are that its retrospective design and the small number of cases.

Conclusion

Colonoscopy is the most important tool for diagnosing and monitoring CRC. Many factors influence the diagnostic quality of colonoscopy. One of the most important factors is adequate colon preparation before colonoscopy. The most important factors affecting colon preparation are education level and age. It has been shown that bowel preparation before colonoscopy is better in patients with a higher education level and in younger patients.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, due to privacy and ethical restrictions. The corresponding author has committed to share the de-identified data with qualified researchers after confirmation of the necessary ethical or institutional approvals. Requests for data access should be directed to bmp.eqco@gmail.com

References

-

Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, Barregard L, Bhutta ZA, Brenner H, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(4):524-48.

-

Allescher HD, Weingart V. Optimizing screening colonoscopy: Strategies and alternatives. Visc Med. 2019;35(4):215-25.

-

Doubeni CA, Laiyemo AO, Major JM, Schootman M, Lian M, Park Y, et al. Socioeconomic status and the risk of colorectal cancer: an analysis of more than a half million adults in the National Institutes of Health‐AARP Diet and Health Study. Cancer. 2012;118(14):3636-44.

-

Doubeni CA, Major JM, Laiyemo AO, Schootman M, Zauber AG, Hollenbeck AR, et al. Contribution of behavioral risk factors and obesity to socioeconomic differences in colorectal cancer incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(18):1353-62.

-

Klabunde CN, Cronin KA, Breen N, Waldron WR, Ambs AH, Nadel MR. Trends in colorectal cancer test use among vulnerable populations in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(8):1611-21.

-

Cronin KA, Scott S, Firth AU, Sung H, Henley SJ, Sherman RL, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, part 1: National cancer statistics. Cancer. 2022;128(24):4251- 84.

-

Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(1):12-49.

-

Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Kaltenbach T, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: Recommendations for physicians and patients from the U.S. Multi- Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86(1):18-33.

-

Kurlander JE, Sondhi AR, Waljee AK, Menees SB, Connell CM, Schoenfeld PS, et al. How Efficacious Are Patient Education Interventions to Improve Bowel Preparation for Colonoscopy? A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164442.

-

Jawa H, Mosli M, Alsamadani W, Saeed S, Alodaini R, Aljahdli E, et al. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for inpatient colonoscopy. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017;28(6):460-64.

-

Reumkens A, Rondagh EJ, Bakker CM, Winkens B, Masclee AA, Sanduleanu S. Post- Colonoscopy Complications: A Systematic Review, Time Trends, and Meta-Analysis of Population-Based Studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(8):1092-101.

-

Shahini E, Sinagra E, Vitello A, Ranaldo R, Contaldo A, Facciorusso A, et al. Factors affecting the quality of bowel preparation for colonoscopy in hard-to-prepare patients: Evidence from the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29(11):1685-707.

-

Amitay EL, Niedermaier T, Gies A, Hoffmeister M, Brenner H. Risk Factors of Inadequate Bowel Preparation for Screening Colonoscopy. J Clin Med. 2021;10(12):2740.

-

Chung YW, Han DS, Park KH, Kim KO, Park CH, Hahn T, et al. Patient factors predictive of inadequate bowel preparation using polyethylene glycol: a prospective study in Korea. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43(5):448-52.

-

Gkolfakis P, Tziatzios G, Papanikolaou IS, Triantafyllou K. Strategies to Improve Inpatients’ Quality of Bowel Preparation for Colonoscopy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2019;1:5147208.

-

Hochberg I, Segol O, Shental R, Shimoni P, Eldor R. Antihyperglycemic therapy during colonoscopy preparation: A review and suggestions for practical recommendations. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7(6):735-40.

-

Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, Fix OK, Jacobson BC. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(3):620-5.

-

Gimeno-García AZ, Baute JL, Hernandez G, Morales D, Gonzalez-Pérez CD, Nicolás-Pérez D, et al. Risk factors for inadequate bowel preparation: a validated predictive score. Endoscopy. 2017;49(06):536-43.

-

Selehi S, Leung E, Wong L. Factors affecting outcomes in colonoscopy. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2008;31(1):56-63.

-

Jacobson BC, Calderwood AH. Measuring bowel preparation adequacy in colonoscopy- based research: review of key considerations. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91(2):248-56.

-

Lebwohl B, Wang TC, Neugut AI. Socioeconomic and other predictors of colonoscopy preparation quality. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2014-20.

-

Heppner H, Christ M, Gosch M, Mühlberg W, Bahrmann P, Bertsch T, et al. Polypharmacy in the elderly from the clinical toxicologist perspective. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;45(6):473-8.

-

Chan WK, Saravanan A, Manikam J, Goh KL, Mahadeva S. Appointment waiting times and education level influence the quality of bowel preparation in adult patients undergoing colonoscopy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:1-9.

-

Serper M, Gawron AJ, Smith SG, Pandit AA, Dahlke AR, Bojarski EA, et al. Patient factors that affect quality of colonoscopy preparation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(3):451-7.

-

Yakut M, Çalğın H. Eğitim Seviyesinin Kolonoskopi Temizlik Başarısındaki Rolu: Retrospektif Değerlendirme. [Role of educational level in colonoscopy cleaning success:ca retrospective evaluation] Maltepe Tıp Dergisi. 2019;11(3):77-80.

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or compareable ethical standards.

Funding

None

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hamidiye Scientific Research (Date: 2024-08-22, No: 24/430)

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Mehmet Eşref Ulutaş, İsmail Hasırcı. The effect of patients’ education level on bowel preparation before a colonoscopy. Eu Clin Anal Med 2024;12(Suppl 1):S15-18

Publication History

- Received:

- September 4, 2024

- Accepted:

- October 8, 2024

- Published Online:

- October 15, 2024

- Printed:

- October 20, 2024