Effectiveness of combination tramadol and tenoxicam versus transdermal fentanyl patches in post-laparotomy

Analgesic effects of tramadol and tenoxicam

Authors

Abstract

Aim This study aimed to compare postoperative pain management protocols and to identify the regimen that minimizes morphine consumption in patients receiving a transdermal fentanyl (TDF) patch, with or without adjunctive tramadol and/or tenoxicam.

Materials and Methods Eighty patients were enrolled in this randomized study. All patients received a TDF patch (50 μg / h) applied 12 hours before surgery, and patient-controlled analgesia with morphine was initiated in the post-anesthetic care unit. Patients were divided into four groups (n = 20 each): Group 1 received no additional analgesia; Group 2 received tramadol 100 mg four times daily; Group 3 received tenoxicam 20 mg once daily; and Group 4 received both tramadol (100 mg four times) and tenoxicam (20 mg once). Demographic data, hemodynamic parameters, Ramsay Sedation Scale (RSS), resting and mobilization visual analog scale (VAS)

scores, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, side effects, and morphine consumption were recorded over 24 hours.

Results Morphine consumption differed significantly between groups at each 6-hour interval, with Groups 1 and 4 showing significantly different consumption compared with the other groups (p < 0.05). Resting VAS scores were lower in Group 1 compared with Group 4 at the 2nd and 4th hours (p < 0.05). Oxygen saturation values were significantly lower in Group 1 at the 1st and 2nd postoperative hours compared with Groups 2 and 4 (p < 0.05). Combined tramadol and tenoxicam administration resulted in lower pain scores at multiple time points.

Discussion Tramadol or tenoxicam alone provided comparable postoperative analgesia, whereas their combined use resulted in more effective pain control without increasing complication rates.

Keywords

Introduction

Today, patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) prepared with opioids is widely used in postoperative pain control, but side effects such as nausea-vomiting, dizziness, respiratory depression, hypotension and urinary retention may occur 1.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the combination of paracetamol or opioid and NSAID is considered the second step, depending on increasing pain severity 2. Pain mechanism have different pathways. Therefore, it may be difficult to provide effective analgesia with a single drug. With the combination of different groups of analgesic drugs, more effective analgesia and fewer side effects can be achieved at lower doses by targeting both central and peripheral pathways. Various pain management guidelines for postoperative analgesia have been developed in the last 20 years, but drug combination studies are still needed 3,4.

Intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) stands out as the recently preferred method in systemic application. Opioids (tramadol, morphine, fentanyl, alfentanil, meperidine, sufentanil), nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory agents (tenoxicam, ketorolac, ibuprofen, acetaminophen, diclofenac) and ketamine are used in systemic administration 3,4. Tramadol is a racemic compound consisting of two isomers with both opioid and non-opioid activity. Tramadol is now widely used in postoperative pain control because it shows monoaminergic activity. Tramadol is a synthetic opioid that acts through two separate synergistic mechanisms of action. It causes weak µ-opioid receptor activation and reuptake inhibition as a monoamine neurotransmitter in the pain inhibition pathway, such as norepinephrine-serotonin. Tramadol does not usually cause cardiovascular or respiratory depression 5,6.

Tenoxicam belongs to the NSAID group. NSAIDs are popular and widely used in postoperative pain control because they do not cause respiratory depression 7,8.

In our study, we aimed to compare the effectiveness of using tramadol and/or tenoxicam with the application of a transdermal fentanyl patch after laparotomy on postoperative pain control.

Materials and Methods

This prospective randomized study included 80 patients, aged between 18 and 65, who were evaluated as I-II-III according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification in the pre-anesthesia evaluation and would undergo laparotomy surgery. Patients with kidney and liver failure, patients with cardiac problems, patients with a history of allergy to opioids and the drugs to be administered, pregnant women, patients with opioid addiction, patients with chronic lung disease, patients with dermatological disorders, patients weighing less than 50 kg and over 100 kg. Patients with psychiatric disorders were excluded from the study.

The patients included in the study were evaluated preoperatively, one day before the operation, and randomly divided into 4 groups after obtaining written and verbal consent forms. Group 1 (TDF, n = 20) which preoperative transdermal fentanyl patch was applied, Group 2 (TDF + Tramadol, n = 20) which was applied preoperative TDF and postoperative tramadol 100 mg 4 x 1, Group 3 (TDF + Tenoxicam, n = 20) which was applied preoperative TDF and postoperative tenoxicam 20 mg and Group 4 (TDF + Tramadol + Tenoxicam, n = 20), which preoperative TDF was applied and postoperative tramadol 100 mg 4 x 1 and tenoxicam 20 mg were applied. Postoperatively, all patients were planned to be fitted with a PCA device (Group 1: TDF + PCA; Group 2: TDF + 4 X 100 mg Tramadol + PCA; Group 3: TDF + 20 mg Tenoxicam + PCA; Group 4: TDF + 4 X 100 mg Tramadol + 20 mg Tenoxicam + PCA).

Before applying preoperative TDF tape to all patients, systolic arterial pressure (SAP), diastolic arterial pressure (DAP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), resting-mobilized visual analog scale (VAS), Ramsey sedation score (RSS) and peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) values were recorded. Then, 50 μg / h was administered to all patients on the anterior chest wall or arm 12 hours before the operation. Fentanyl (Durogesic 50 μg / h 5TTS Patch, Johnson & Johnson, Istanbul, Turkey) patch was applied, and the patients’ symptoms and findings of nausea, vomiting, bradycardia, dyspnea, diarrhea/constipation and itching were recorded until the operation. No medication was given to the patients for premedication in the preoperative preparation room. The PCA device, which will be installed in the postoperative recovery room, was introduced to all patients, and its use was explained in detail.

The patients underwent electrocardiography (ECG), systolic arterial pressure (SAP), diastolic arterial pressure (DAP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR) and peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) monitoring in standard DII lead. Hemodynamic measurements, sedation scores and VAS values of all patients were recorded in the operating room before induction. The sedation scores of the patients were evaluated with RSS. After preoxygenation (at 10 L / min for 1 min) in the operating room, anesthesia induction (2 mg / kg propofol (Fresenius Kabi, Istanbul, Turkey), 1 μ / kg fentanyl (Tadilat, 0.5 mg, 10 ml, Vem İlaç, Istanbul, Turkey), and 0.6 mg / kg intravenous rocuronium) was administered. The patient was intubated 3 minutes after the muscle relaxant was given. For anesthesia maintenance, 1.5-2% sevoflurane (Sevorane, Abott, Istanbul, Turkey) in 50% O2 + 50% N2O was applied.

As a muscle relaxant maintenance dose, 0.01 mg / kg rocuronium bromide was used when necessary. At the end of the operation, sevoflurane was discontinued, and its muscle relaxant effect was antagonized with atropine (0.01-0.02 mg / kg) and neostigmine (Neostigmine, 0.5 mg / ml, Adeka İlaç, Samsun, Istanbul) (0.04-0.08 mg / kg). When it was determined that their spontaneous breathing was sufficient, the cases were extubated by aspirating oropharyngeal secretions. No postoperative additional medication was given to Group 1, tramadol (Ultramex 100 mg 2 ml, Adeka İlaç, Samsun, Turkey) 100 mg iv was administered to Group 2 and postoperative 3 x 1 tramadol iv was ordered, Group 3 was given tenoxicam (Tenoxicam 20 mg lyophilized vial, Mustafa Nevzat İlaç San. A.Ş., Istanbul, Turkey) was given 20 mg iv, Group 4 was given tramadol 100 mg and tenoxicam 20 mg iv and postoperative 3 x 1 tramadol iv was ordered.

Side effects, resting-mobilized VAS level, nausea-vomiting, diarrhea- constipation, itching and amounts of morphine consumed were recorded at 1, 2, 4, 6, 12 and 24 hours postoperatively. Transdermal fentanyl and PCA device were removed at the 24th postoperative hour. Those whose SpO2 was below 90% within 24 hours, whose heart rate was 50 or less despite the administration of atropine, and whose respiratory rate was 8 or less per minute, had their fentanyl patches and PCA devices removed and were excluded from the study. If necessary, naloxone (Naloxone HCL, 0.4 mg / ml), Abbott Laboratories, Istanbul, Turkey, was planned to be given and antagonized, but it was no longer necessary.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS for Windows version 22.0 package program was used for statistical analysis, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For comparison of numerical measurements in more than two independent groups, ANOVA and LSD tests were used for variables with normal distribution, and Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn tests were used for variables without normal distribution. Relationships between verbal variables were tested with the chi-square test. Repeated measures analysis of variance was applied to test the changes in repeated measurements over time. In power analysis, the minimum sample size required in each group was determined to be 17 in order to find a significant change of 2 ± 2 units in the amount of morphine consumption in the TDF-TRMDL group at the 2nd hour compared to the TDF-OKS group (α = 0.05, 1 - β = 0.80).

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Gaziantep University, Faculty of Medicine (Date: 2014-04-21, No: 152).

Results

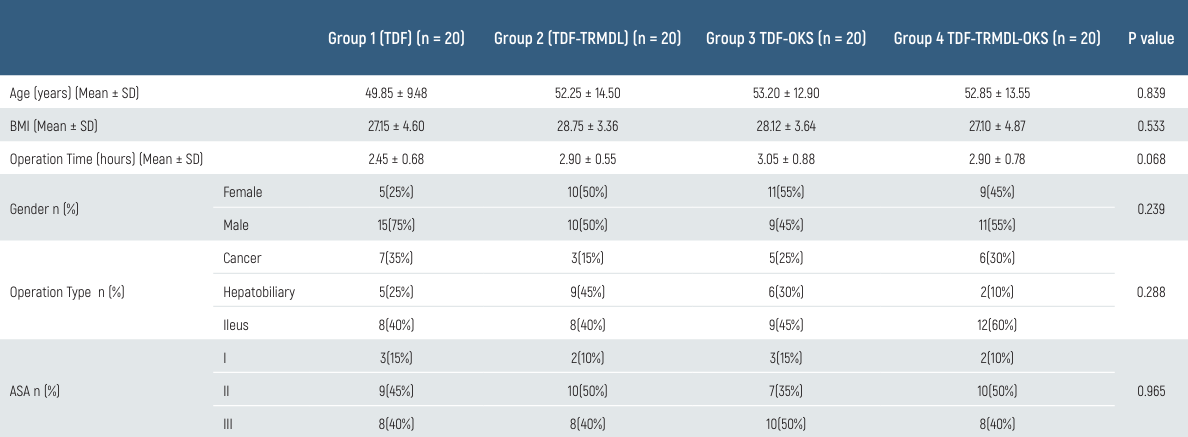

83 patients were included in the study. Three patients were excluded from the study because hypotension developed. All 80 patients completed the study. Demographic data are shown in Table 1. When these data were examined statistically, there was no significant difference between the groups (p > 0.05).

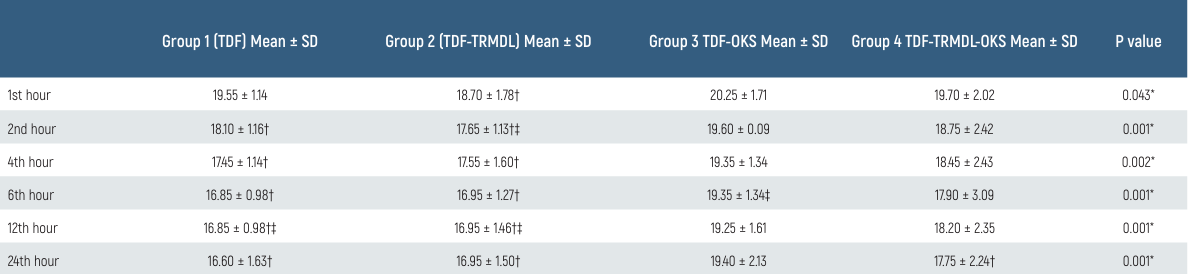

There was no significant difference between the groups in postoperative measurements of hemodynamic parameters SAB, DAB, MAP and HR (p > 0.05). Postoperative respiratory rates of the patients were significantly higher in Group TDF-OKS at all hours than in Group TDF-TRMDL at the 2nd, 4th, 6th, 12th, and 24th hours (p < 0.05). However, Group TDF-OKS was significantly higher than Group TDF-TRMDL-OKS at the 6th and 24th hours (p < 0.05). Group TDF-TRMDL-OKS was significantly higher than Group TDF-TRMDL at the 2nd and 12th hours and compared to Group TDF at the 12th hour (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

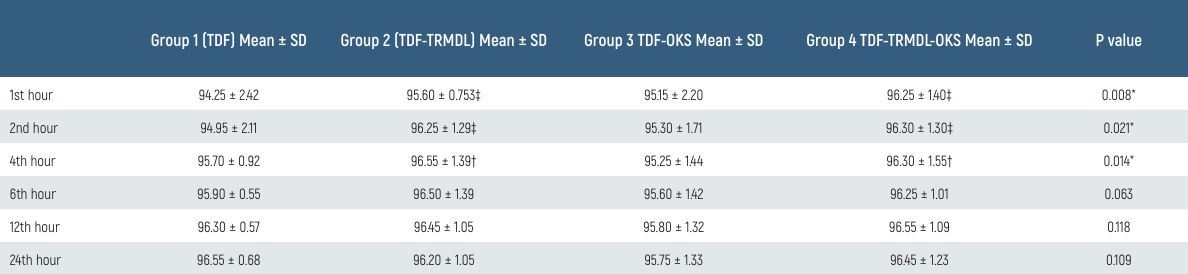

Postoperative saturation values of the patients were significantly lower in Group TDF at the 1st and 2nd hours than in Group TDF-TRMDL and Group TDF-TRMDL-OKS. At the 4th hour, it was significantly lower in Group TDF-OKS than in Group TDF-TRMDL and Group TDF-TRMDL-OKS (p < 0.05) (Table 3).

There was a significant difference between Group TDF and the other 3 groups, and between Group TDF-TRMDL-OKS and the other 3 groups, in the postoperative morphine consumption of the patients at every 6 hours of follow-up (p < 0.05). Morphine consumption was higher in Group TDF and lower in Group TDF-TRMDL-OKS.

Postoperative resting VAS values of the patients were significantly lower in Group TDF than in Group TDF-TRMDL-OKS at the 2nd and 4th hours (p < 0.05).

All patients were on the 1st, 2nd, 4th, 6th, 12th and 24th postoperative days. Clinical findings of nausea, vomiting, itching, and diarrhea- constipation were recorded. The statistical result obtained by the chi- square test was insignificant (p > 0.05).

Discussion

Postoperative respiratory rates were clinically higher at certain time points in the TDF-OKS and TDF-TRMDL-OKS groups compared with the other groups. Similarly, postoperative oxygen saturation levels were clinically lower at some hours in the TDF and TDF-OKS groups. A significant difference in postoperative morphine consumption was observed between the TDF group and the other three groups, as well as between the TDF-TRMDL-OKS group and the remaining groups, at each 6-hour interval. Morphine consumption was highest in the TDF group and lowest in the TDF-TRMDL-OKS group. Resting VAS scores were significantly lower in the TDF group than in the TDF-OKS group at the 2nd and 4th postoperative hours.

Many methods have been described for postoperative pain management. These include patient-controlled analgesia (intravenous and epidural), transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, and continuous spinal or epidural analgesia as current approaches. But these systems also increase costs 9. Today, opioid-prepared PCA is widely used in postoperative analgesia. However, side effects such as nausea, vomiting, dizziness, hypotension, respiratory depression and urinary retention may occur 10. For this reason, in our study, the second-step treatment method (tramadol and/or tenoxicam), which is a combination of paracetamol or opioid and NSAID, was used as mentioned in the WHO analgesia treatment pattern ladder.

In the study by Mimic et al., intravenous tramadol was used for preemptive analgesia in patients undergoing ureteroscopic lithotripsy for unilateral ureteral stones. Patients were randomized to receive either 100 mg tramadol in 500 mL 0.9% NaCl or saline alone preoperatively. VAS scores and the need for rescue diclofenac were recorded. Although first-hour postoperative VAS scores were significantly lower in the tramadol group, no difference was observed at later time points. Tramadol was considered safe due to the absence of respiratory or cardiac depression 11. In our study, tramadol was preferred for its safety profile. Based on the limited duration of effect reported by Mimic et al., tramadol was administered every 6 hours postoperatively. Morphine consumption was significantly higher in the TDF group than in the TDF-TRMDL group at all postoperative time points, while no significant differences were observed in VAS scores, complication rates, hemodynamic variables, or respiratory parameters. These findings further support the efficacy and safety of tramadol in postoperative pain management without increasing adverse effects. Choi et al. compared fentanyl-based PCA with intravenous tramadol for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer. In this study, including 261 patients, one group received fentanyl-PCA, while the other received IV tramadol on demand based on VAS scores, with ketorolac added if necessary. Postoperative hospital stay was significantly longer, and anesthesia-related costs were higher in the PCA group. The authors concluded that fentanyl-PCA was not essential for effective postoperative analgesia, as comparable pain control could be achieved with IV tramadol, with fewer side effects and lower costs 12. In our study, tramadol and/or tenoxicam were administered in combination with a transdermal fentanyl patch to reduce the need for IV morphine PCA in laparotomy patients. Morphine consumption was significantly lower at all postoperative time points in the adjunct treatment groups compared with the TDF-only group, thereby minimizing PCA-related disadvantages.

Sathitkarnmanee et al. evaluated the efficacy of a transdermal fentanyl (TDF) patch for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. In this randomized study of 40 patients, a 50 μg / h TDF patch was applied 12 hours preoperatively in one group, while the control group received a placebo patch; all patients were managed with morphine PCA for 48 hours. The authors demonstrated that preoperative TDF significantly reduced postoperative pain scores and morphine consumption without increasing adverse effects 13. In our study, morphine consumption via PCA was used as the primary objective indicator of analgesic efficacy. To minimize opioid-related complications, a 50 μg / h TDF patch was applied preoperatively in all groups. Consistent with the findings of Sathitkarnmanee et al., this approach contributed to reduced overall morphine requirements and may have mitigated opioid-related respiratory and cardiovascular side effects.

Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scoring has become a safe method due to its ease of use, validity and reliability in defining the severity and intensity of pain. A VAS score below 4 is an acceptable analgesic level 14,15,16. In a study conducted by Russo et al., patients who underwent laparotomy were compared with IVHKA prepared with morphine and ketorolac for postoperative analgesia control with patients administered IV morphine HKA and IV ketorolac. As a result of the study, VAS values were lower at all hours, and side effects such as analgesic requirement and nausea and vomiting were less in the Ketoralac IV push group compared to the infusion group. It was concluded that intravenous administration of ketorolac at regular intervals (8 hours apart) provides more effective analgesia than continuous infusion. Ketorolac is an NSAID commonly used for postoperative pain control. The advantages of NSAIDs in pain control after laparotomy have been reported in many studies 17,18,19. We also used VAS as a pain scoring system in our study. In our study, since the average VAS value in all groups and hours except Group TDF- TRMDL-OKS 1st hour was 4 and below, we can say that we provided effective analgesia for 24 hours postoperatively in all four groups.

Chandanwale et al. compared the efficacy and safety of tramadol– paracetamol and tramadol–diclofenac combinations in postoperative pain, acute osteoarthritic exacerbations, rheumatoid arthritis, and acute musculoskeletal disorders. In this randomized study of 204 patients, the tramadol–diclofenac combination provided superior analgesia with fewer side effects, indicating that diclofenac was a more appropriate NSAID than paracetamol in these settings 20. In our study, tenoxicam was preferred instead of paracetamol in combination with tramadol as a second-step analgesic strategy. The combined use of tramadol and tenoxicam achieved comparable analgesia with significantly lower morphine consumption in the TDF-TRMDL-OKS group compared with groups receiving tramadol or tenoxicam alone, without an increase in complication rates.

Ural et al. compared oral, intramuscular, and transdermal diclofenac sodium for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. VAS scores were significantly lower in the intramuscular and transdermal groups compared with the oral group at all time points, and tramadol consumption was also reduced in these groups. The authors concluded that transdermal diclofenac provided analgesic efficacy comparable to intramuscular administration and superior to oral use 21. In our study, intravenous tenoxicam was preferred as the NSAID component of postoperative analgesia.

Das et al. compared the efficacy and safety of lornoxicam and tramadol for postoperative analgesia following head and neck surgery and demonstrated that lornoxicam was as effective and safe as tramadol 22. In our study, tenoxicam—another oxicam-derived NSAID—was used, and no significant differences were observed between the TDF-TRMDL and TDF-OKS groups in terms of mean VAS scores at any time point, total morphine consumption, or side effect rates.

Su et al. investigated the effect of flurbiprofen on postoperative pain control after thymectomy in patients with myasthenia gravis and demonstrated that flurbiprofen was effective and safe for post- thymectomy analgesia 23. In our study, no statistically significant difference was observed in mean morphine consumption between tenoxicam and tramadol at any postoperative time point. However, unlike the findings of Su et al., morphine consumption tended to be lower in the tramadol group, while complication rates were comparable between groups.

Shankariah et al. compared ketorolac and tramadol for postoperative analgesia following maxillofacial surgery and reported that intramuscular tramadol provided superior analgesic efficacy 24. In our study, no significant difference was found in side effect rates between tramadol and tenoxicam. In contrast to Shankariah et al., analgesic efficacy assessed by morphine consumption did not differ significantly between tramadol and tenoxicam.

Tables

Table 1. Comparison of groups according to demographic data

Table 2. Comparison of groups according to postoperative respiratory rate values

* p < 0.05; † p < 0.05 vs TDF-OKS; ‡ p < 0.05 vs TDF-TRMDL-OKS

Table 3. Comparison of groups according to postoperative SPO2 values

* p < 0.05; † p < 0.05 vs TDF-OKS; ‡ p < 0.05 vs TDF

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. The limited number of patients in our study, short follow-up period, generalizability of study findings and the nonhomogeneous injury patterns can be considered among the limitations of our study.

Conclusion

Since the effectiveness and complications of many drugs and methods used for postoperative pain control vary, appropriate drug combination studies continue to be controversial. There was no change in the hemodynamic parameters in the postoperative analgesia control of the use of tramadol and/or tenoxicam, accompanied by TDF patch application. The use of tramadol and tenoxicam alone provided equal analgesia, while their use together provided more effective analgesia and did not change the complication rate. The combination of tramadol and/or tenoxicam, accompanied by TDF patch application, can be used safely in postoperative pain management control.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

-

Michelet F, Smyth M, Lall R, et al. Randomised controlled trial of analgesia for the management of acute severe pain from traumatic injury: study protocol for the paramedic analgesia comparing ketamine and morphine in trauma (PACKMaN). Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2023;31(1):84. doi:10.1186/s13049-023-01146-1.

-

Zhang A, Zhou Y, Zheng X, et al. Effects of S-ketamine added to patient-controlled analgesia on early postoperative pain and recovery in patients undergoing thoracoscopic lung surgery: a randomized double-blinded controlled trial. J Clin Anesth. 2024;92:111299. doi:10.1016/j.jclinane.2023.111299.

-

Su P, Liu Y, Zhang L, Bai LB. Comparison of analgesia treatment methods after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a network meta-analysis of 42 randomized controlled trials. Orthop J Sports Med. 2023;11(5):23259671231167128. doi:10.1177/23259671231167128.

-

Akbari GA, Erdi AM, Asri FN. Comparison of Fentanyl plus different doses of dexamethasone with Fentanyl alone on postoperative pain, nausea, and vomiting after lower extremity orthopedic surgery. Eur J Transl Myol. 2022;32(2):10397. doi:10.4081/ejtm.2022.10397.

-

Tascon Padron L, Emrich NLA, Strizek B, et al. Implementation of a piritramide based patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) as a standard of care for pain control in late abortion induction: a prospective cohort study from a patient perspective. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X. 2023;20:100251-56. doi:10.1016/j.eurox.2023.100251.

-

Xie D, Liu F, Zuo Y. Effectiveness of sufentanil-based patient-controlled analgesia regimen in children and incidence of adverse events following major congenital structure repairs. J Clin Pharmacol. 2023;63(6):715-20. doi:10.1002/jcph.2211.

-

Orbay Yasli S, Jr., Gunay Canpolat D, Dogruel F, Demirbas AE. Efficacy of tenoxicam, paracetamol, and their combination in postoperative pain after double-jaw surgery. Cureus. 2023;15(8). doi:10.7759/cureus.44195.

-

Sahin GK, Gulen M, Acehan S, Satar DA, Erfen T, Satar S. Comparison of intravenous ibuprofen and tenoxicam efficiency in ankle injury: a randomized, double-blind study. Ir J Med Sci. 2023;192(4):1737-43. doi:10.1007/s11845-022-03159-8.

-

Kim S, Song IA, Lee B, Oh TK. Risk factors for discontinuation of intravenous patient- controlled analgesia after general surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):18318. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-45033-2.

-

Wang Y, Wu G, Liu Z, et al. Effect of oxycodone combined with ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral nerve block on postoperative analgesia in patients with lung cancer undergoing thoracoscopic surgery: protocol for a randomised controlled study. BMJ Open. 2023;13(10):e074416. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2023-074416.

-

Mimic A, Dencic N, Jovicic J, et al. Pre-emptive tramadol could reduce pain after ureteroscopic lithotripsy. Yonsei Med J. 2014;55(5):1436-41. doi:10.3349/ymj.2014.55.5.1436.

-

Choi YY, Park JS, Park SY, et al. Can intravenous patient-controlled analgesia be omitted in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer? Ann Surg Treat Res. 2015;88(2):86-91. doi:10.4174/astr.2015.88.2.86.

-

Sathitkarnmanee T, Tribuddharat S, Noiphitak K, et al. Transdermal fentanyl patch for postoperative analgesia in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. J Pain Res. 2014;7:449-54. doi:10.2147/JPR.S66741.

-

Yadav U, Doneria D, Gupta V, Verma S. Ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block versus single-shot epidural block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing inguinal hernia surgery. Cureus. 2023;15(1):e33876. doi:10.7759/cureus.33876.

-

Omara AF, Ahmed SA, Abusabaa MM. The effect of the use of pre-emptive oral pregabalin on the postoperative spinal analgesia in patients presented for orthopedic surgeries: randomized controlled trial. J Pain Res. 2019;12:2807-14. doi:10.2147/JPR.S216184.

-

John R, Ranjan RV, Ramachandran TR, George SK. Analgesic efficacy of transverse abdominal plane block after elective cesarean delivery - bupivacaine with fentanyl versus bupivacaine alone: a randomized, double-blind controlled clinical trial. Anesth Essays Res. 2017;11(1):181-4. doi:10.4103/0259-1162.186864.

-

Russo A, Di Stasio E, Bevilacqua F, Cafarotti S, Scarano A, Marana E. Efficacy of scheduled time ketorolac administration compared to continuous infusion for post-operative pain after abdominal surgery. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(12):1675-9.

-

Aguilar B, Penm J, Liu S, Patanwala AE. Efficacy and safety of transdermal buprenorphine for acute postoperative pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2023;24(11):1905-14. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2023.07.001.

-

Degala S, Nehal A. Comparison of intravenous tramadol versus ketorolac in the management of postoperative pain after oral and maxillofacial surgery. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;22(3):275-80. doi:10.1007/s10006-018-0700-3.

-

Chandanwale AS, Sundar S, Latchoumibady K, et al. Efficacy and safety profile of combination of tramadol-diclofenac versus tramadol-paracetamol in patients with acute musculoskeletal conditions, postoperative pain, and acute flare of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: a Phase III, 5-day open-label study. J Pain Res. 2014;7:455-63. doi:10.2147/ JPR.S67817.

-

Gulcin Ural S, Yener O, Sahin H, Simsek T, Aydinli B, Ozgok A. The comparison of analgesic effects of various administration methods of diclofenac sodium, transdermal, oral and intramuscular, in early postoperative period in laparoscopic cholecystectomy operations. Pak J Med Sci. 2014;30(1):96-100. doi:10.12669/pjms.301.4140.

-

Das SK, Banerjee M, Mondal S, Ghosh B, Ghosh B, Sen S. A comparative study of efficacy and safety of lornoxicam versus tramadol as analgesics after surgery on head and neck. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;65(Suppl 1):126-30. doi:10.1007/s12070-013-0617-y.

-

Su C, Su Y, Chou CW, et al. Intravenous flurbiprofen for post-thymectomy pain relief in patients with myasthenia gravis. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;7:98. doi:10.1186/1749-8090-7-98.

-

Shankariah M, Mishra M, Kamath RA. Tramadol versus ketorolac in the treatment of postoperative pain following maxillofacial surgery. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2012;11(3):264-70. doi:10.1007/s12663-011-0321-y.

Scientific Responsibility Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content, including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, and some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents, and approval of the final version of the article.

Animal and Human Rights Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Gaziantep University, Faculty of Medicine (Date: 2014-04-21, No: 152)

Additional Information

Publisher’s Note

Bayrakol MP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional and institutional claims.

Rights and Permissions

About This Article

How to Cite This Article

Vahap Saricicek, Cigdem Koni. Effectiveness of combination tramadol and tenoxicam versus transdermal fentanyl patches in post-laparotomy. Eu Clin Anal Med 2026;14(1):10-14

Publication History

- Received:

- December 11, 2025

- Accepted:

- December 11, 2025

- Published Online:

- December 31, 2025

- Printed:

- January 1, 2026